The city itself is the collective memory of its people, and like memory, it is associated with objects and places. The city is the locus and the citizenry becomes the city’s predominant image, both of architecture and of landscape, and as certain artifacts become part of its memory, new ones emerge. In this entirely positive sense, great ideas flow through the history of the city and give shape to it.’

[1, p. 130] from Aldo Rossi, The Architecture of the City

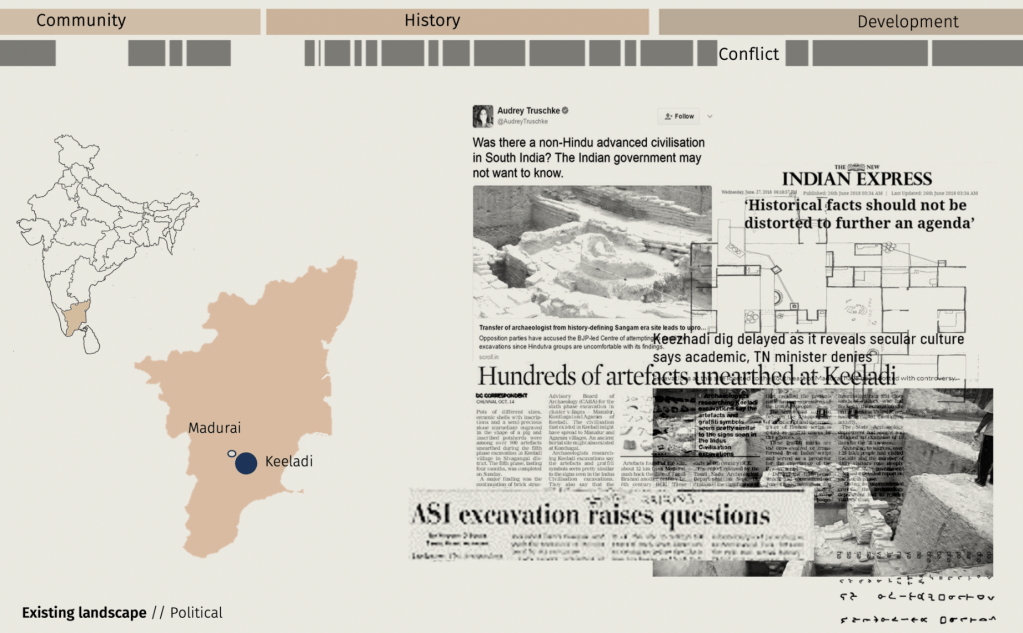

In 2018, I presented my undergraduate thesis titled: Transforming landscapes: Architecture of Archaeology. It was a difficult project to complete during the time since it was embedded in the politics of the archaeological excavations in Keeladi and these were terrains architecture students were not allowed to enter. We were supposed to design neutral buildings devoid of the politics of the place. It has been seven years since and the Superintendent Archaeologist in charge of the excavations from 2014-2016, K. Amarnath Ramakrishna who had two years earlier submitted a 982-page report on the findings has been asked by Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) to revise the dating of the Keeladi civilisation for ‘authenticity’. What does ASI deem as authentic and why contest the dating NOW?

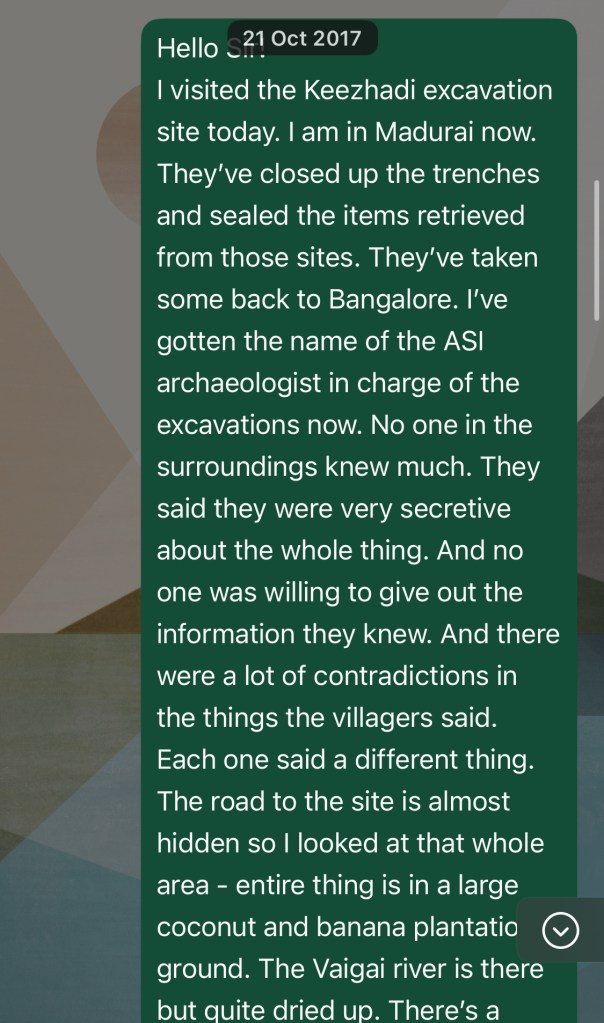

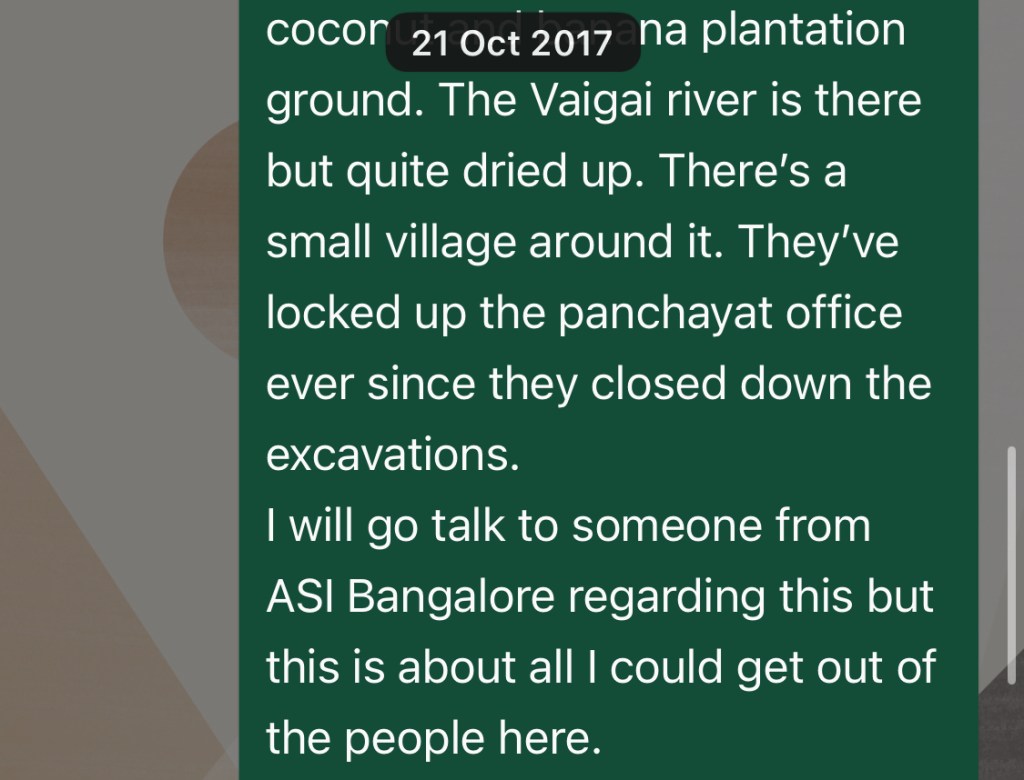

For some context – in October of 2017, I visited Keeladi to understand what was uncovered during the two phases of excavation only to find no trace of ongoing work – the trenches were abruptly closed overnight without any intimation or announcement. The artefacts retrieved were locked inside the Panchayat office without informing the residents in the area. One of the farmers said that the whole excavation was conducted in secrecy and there were a lot of contradicting information shared with the local residents. Moreover, the artefacts then were quietly transported to Bangalore in the night to avoid raising alarms. The question at the time was what had they found that made them not share a detailed report as they should have that year. The report was finally sent to ASI only in 2023, 6 years after the time I went around asking around for it at the ASI Bangalore office. I was in constant touch with an archaeologist from the Bangalore office to find out if anything was published regarding this for the next few years, but all I could get were initial articles published in 2016 and then there was silence.

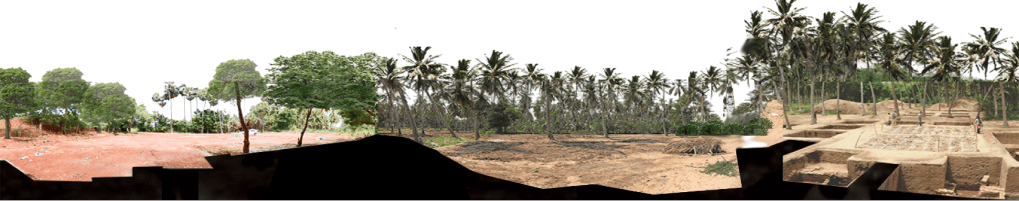

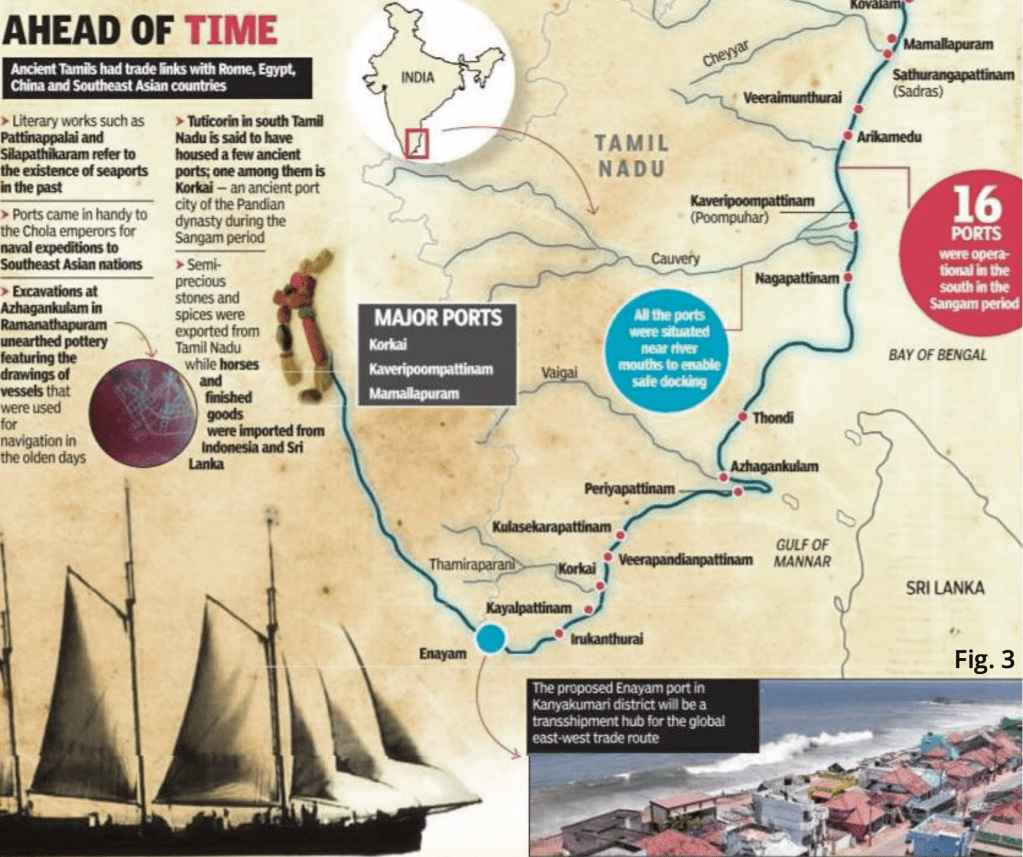

The excavations which began in 2014 at Keeladi, after identifying 293 potentially archaeologically rich sites along the banks of the Vagiai River, were then been abandoned indefinitely after ASI Bangalore handed over the authority to the the Tamil Nadu State Government. The excavations (under the ASI) which saw three phases of uncovering, established a settlement dating as far back as 800 BCE, pushing back the previously accepted timeline (300 BCE to 200 CE) for this period of Tamil culture. Over two years, the ASI team unearthed nearly six thousand artefacts from 102 trenches, making it one of the largest excavations of its kind in Tamil Nadu. The discoveries showed evidence of a sophisticated urban civilisation dating back to the Sangam era with brick structures, advanced drainage systems made of terracotta pipes, ring wells (indicative of urban living), furnaces suggesting industrial activity (like silk dyeing, a tradition still alive locally), pottery with Tamil Brahmi inscriptions from around 200 BCE (indicating common literacy), ivory dice, gold beads, and even trade indicating possible links to the Indus Valley Civilisation. It thrived on the banks of the erstwhile Manalur Lake which is now currently dry and doubles as plantation fields.

Since the first phase of excavations began in Keeladi, evidence has strongly pointed that the settlements did not align withthe dominant, Vedic-centric timelines favoured by the regime in power since 2014. However, with the report finally presented a few years ago, that dating of some of the artefacts were made abundantly clear.

Although it was hard to connect the dots then – there is a deeper ideological and institutional tension between ASI and the Keeladi excavation. The Caravan’s exhaustive investigative report titled “How the Archaeological Survey of India fortifies Hindutva History” discusses at length this ideological tilt in the ASI’s recent work. After the dating of Keeladi came back the first time from foreign laboratories, and the report was to be submitted, the Superintendent Archaeologist in charge was transferred to Assam, midway of the excavation phase. In this context, ASI’s pushback against Ramakrishna’s report seems less about questioning the accuracy of the dating in itself and more about discomfort with the implications of pre-Vedic origins of Keeladi; the fact that it challenges the long held notion that civilisational advancement in India originated during the Vedic times.

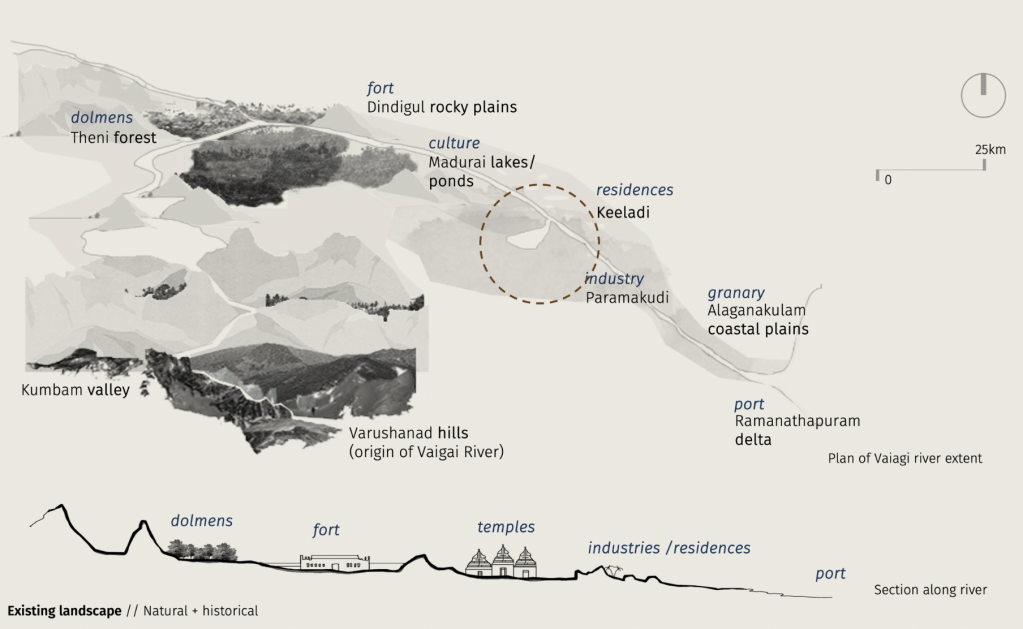

For my thesis, I conducted research in the Keeladi area, but also the larger context connecting it to Sangam landscapes.

Context setting from 21 year old Namrata:

The natural features along the river is what characterise the Vaigai River Valley Civilisation. From mountains to valleys to forests to dry plateaus to agricultural fields and finally to the sea. The excavations have uncovered burial mounds to forts to industrial towns and to large scale ports. These finds have been so fragmented until the 293 continuous stretch of potential sites were mapped out by the Archaeological Survey of India and excavations began in 2014 to uncover the centre of this 2500 year old expanding civilisation.

Narendra, N. (2018). Transforming Landscapes, the architecture of archaeology. (Unpublished Thesis).

The site is 10 km away from Madurai, set a couple kilometres inwards to the south of the National Highway. It is an almost flat land with three small villages of a population of 3000 in total, working on agricultural farmlands and coconut groves. The site has developed around an earlier existing Manalur Lake which has been dry for several years now.

At a time when the political bodies of a city are what dictate our knowledge and awareness about a majority of issues, there is a dilemma about the future of ruins in the contemporary culture. The new learnings we uncover everyday about our country and about the world is something that shouldn’t be hidden under layers of jingoism or political gamesmanship.

The landscapes that have been written and discussed haven’t had much translation into actual maps or drawings. However, the area around Keeladi had been a part of the Pandya kingdom and also said to have been the capital at one point in time. The Sangam texts refer to five different landscape. 1 – Kurinji (Hills), 2- Palai (Dry lands), 3- Mullai (Woodlands) 4- Marutam (fertile plains), 5- Neytal (River beds and Sea). The Kuruntogai, a collection of 401 short poems, was written during the Sangam period of Tamil literature describing these landscapes —->

Kurinji (hills)

…the land of mountains lying range upon range where torrents rush down the mountainside like snakes slithering to ground, crashing into boulders and tearing at the tall stout trunks of the venkai trees which grow among the rocks leaving their swaying blossom-laden branches empty. (poem 110)

Palai (dry lands)

…that waterless desert where in the last days of spring the tem and tumpi beetles suck on a single cluster of blossom in the hot, upraised branches of a scorched, stunted kadambu tree, and come away still hungry. (p 211)

Mullai (woodland)

Evening, with its clouds of flying insects, is upon the woodlands, my friend, but see, he has not returned, he who left to seek his fortune. (p 220)

Marutam (fertile plains)

…The hill farmers have reaped their broad fields of small-eared millet and planted a second crop of avarai beans

(p 82)

Neytal (seashore)

…our pretty little village where the ocean’s waves, smelling of fish and the dark shoreline forests meet like moonlight and darkness, and where the fronds of young palmyra trees bend invitingly to the ground… (p 81)

(Source: Kuruntogai, Robert Butler, 2010 via Uma Sankar Sekar)

The 2,000-year-old site of Keeladi in Tamil Nadu must be understood within the broader context of civilisational continuity – from the Harappan period to the so-called second Urbanisation along the Gangetic plains. Rather than treating it as an outlier, Keeladi should be seen as part of a larger, pan-Indian historical landscape. In India, archaeology has long been caught in the crossfire between evidence and myth. This tension isn’t confined to colonial Indologists or Marxist historians alone but now comes with the added friction of fake news, hindutva ideologies and distorted narratives.

In Keeladi, this complexity deepens with assertions of a direct Harappan-Tamil lineage. While culturally resonant, such claims (with no evidence) risk isolating localised archaeology from its national context and weaponising it for certain ideologies. Amid these debates and arguments, Keeladi is critical and any discoveries have to be handled with honesty and care. Keeladi holds the potential to reshape how we think about India’s past and how we understand our country’s collective memories.

I am now reflecting on why I had chosen to study and use this as a context for my design during my undergraduate degree. This was my motivation –

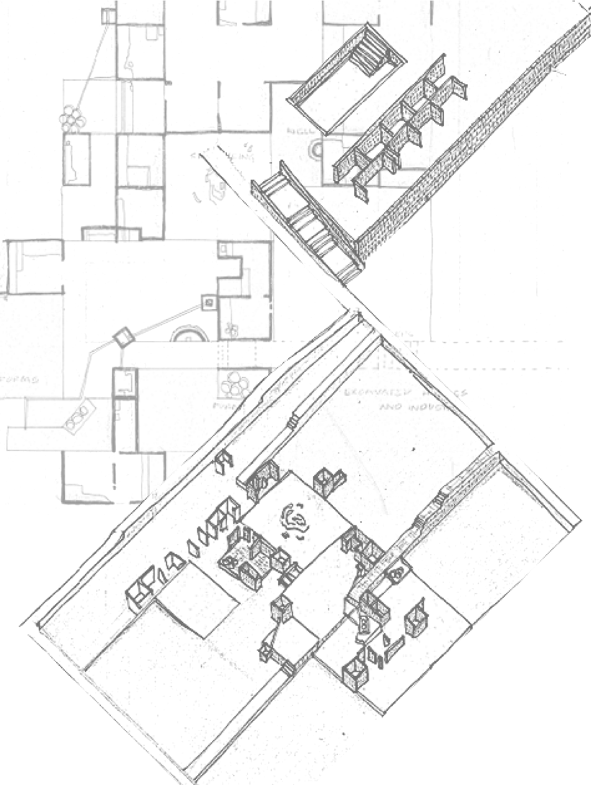

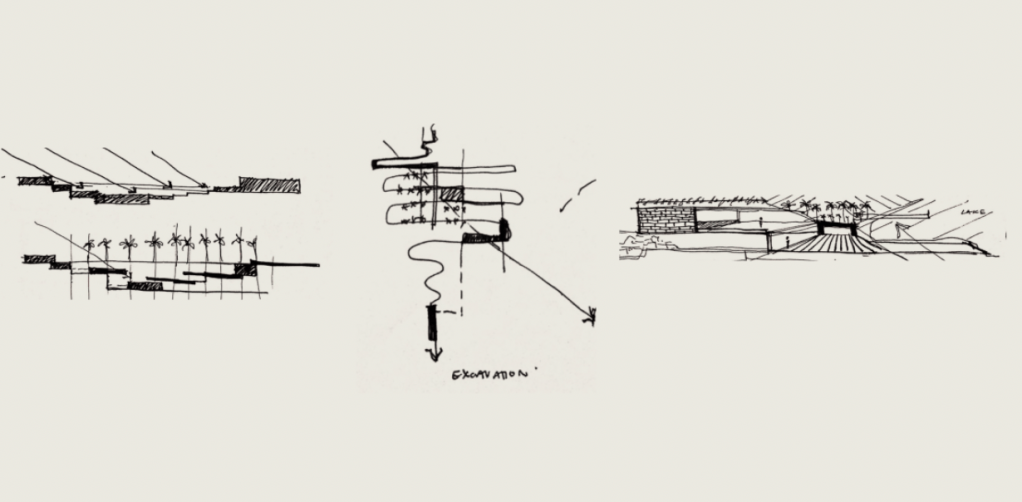

The identities of architecture and archaeology have always been contrasting – the former builds up while the latter breaks down or cuts away. However, their implicit and explicit relationship has been grossly overlooked for the past decades and it is in this in-between grey area that the project finds itself situated, as part of the same field of study and research. The landscape that has been cut away in archaeology is the architecture of a by- gone time. In simpler terms, time and the extent of transformation is being stratified. Architecture in essence, is stratification of space. This leads to an exploration of the notion that the process of archaeological excavation is also a way of making architectural space. Then what would be the level of sensitivity required to contain the existing layers of a transformed site wrapped in its own narratives and induce into it the current landscape? Is there a way to showcase our evolution through the passage of time? Keeladi in Tamil Nadu, the site in question is a village that is living over the remains of an earlier, bigger city of a glorious era. Peru Manalur as the city used to be called was the older Madurai city. The thesis is a design-based investigation that proposes the convergence of the architectural and archaeological landscapes. It represents an attempt to avoid drastically altering the original landscape of an archaeological site, by closely studying the archaeological finds and placing it across time and space, merging it with the current landscape, to foster a unified collective memory, removed from the unnecessities of politics and conflict. This Project aims to propel further the necessities of discussions and dialogue that come with such changes.

Snippets from my design project can be found here.

Edit as of May 25th: K. Amarnath Ramakrishna has responded to the ASI that he stands by the findings in his report and will not revise them. (The Hindu)