Research poster presented at the TU Delft Climate Action Festival, June 2024

In addition, science fiction literature and media helped point to interesting metaphors of spatial justice. For instance, the show “Snowpiercer” depicts how survivors of a climate catastrophe, aboard a sealed train, reproduce hierarchical divisions through competition for engine control. This imagery served as the initial inspiration for conceiving cities as vessels on the move, such as trains or ships, whose trajectories are guided by powerful actors making decisions on the changing climate.

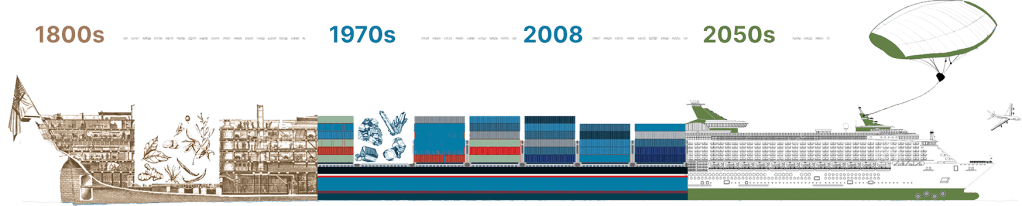

The idea behind the metaphor was to reflect on the complex relationship between cities and climate change. The narrative of the metaphor was strengthened by building a sequence that understood the ship temporally, socially and politically. A constellation of seafaring, navigation and ship building elements supported the visual logic of understanding the ship from different angles, much like urbanisation processes. An example of this was the analogous process of a ship constructed deck by deck to a city built over time through successive layers of infrastructure and utility networks . A ship’s spatial, economic, and social stratification was highlighted to represent both city and global stratification.

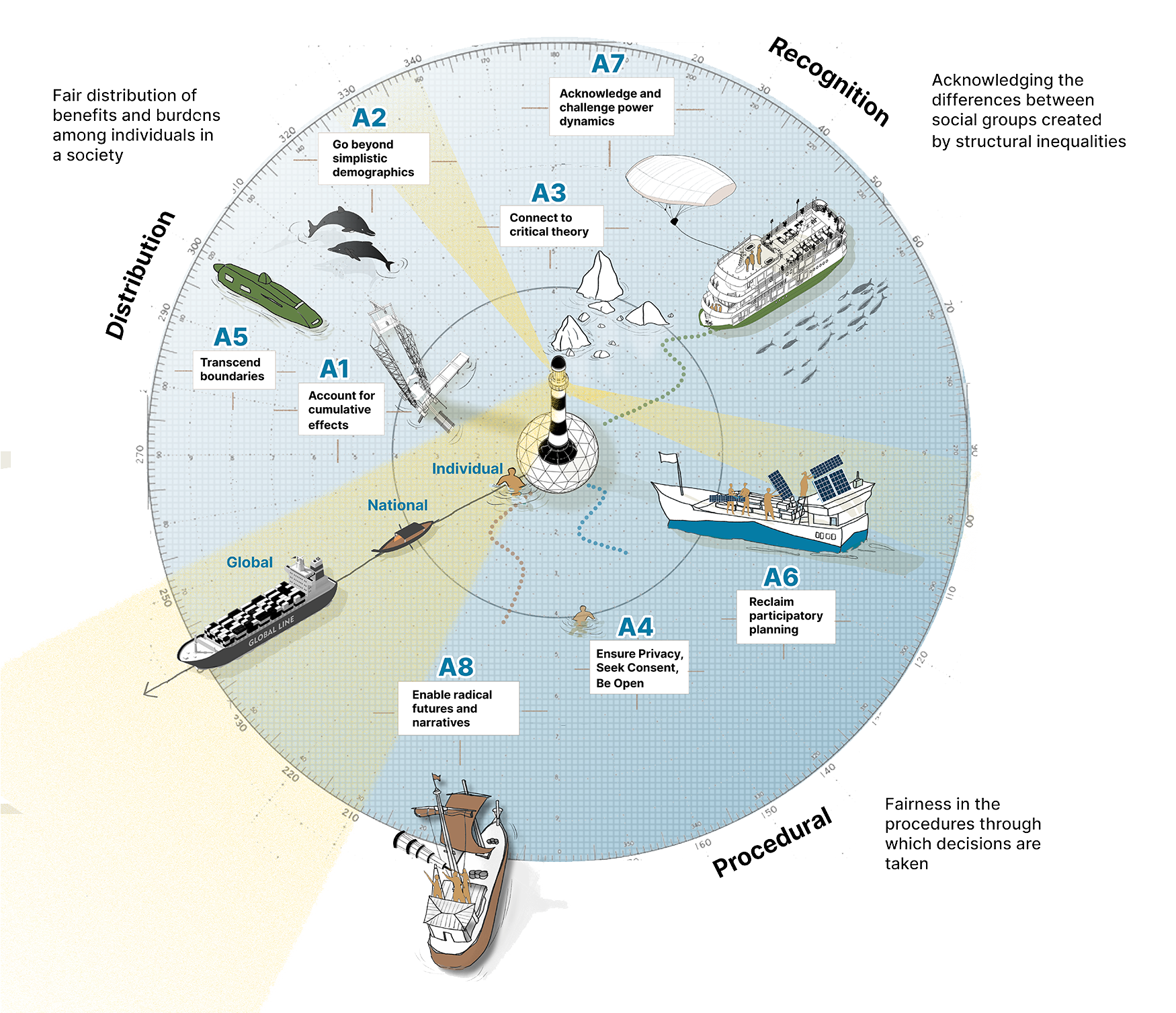

The concluding visual that represents the avenues for spatial justice in urban climate action evokes the image of a ship’s radar to represent how cities can navigate climate change through spatially just principles. Through this analogy, urban polities are shown as ships/vessels guided by the eight different principles presented in the paper. A lighthouse was incorporated to signify a universal symbol of seafaring guidance that also doubled up to clearly distinguish between the different dimensions of justice (i.e., distributive, procedural, and recognition justice).

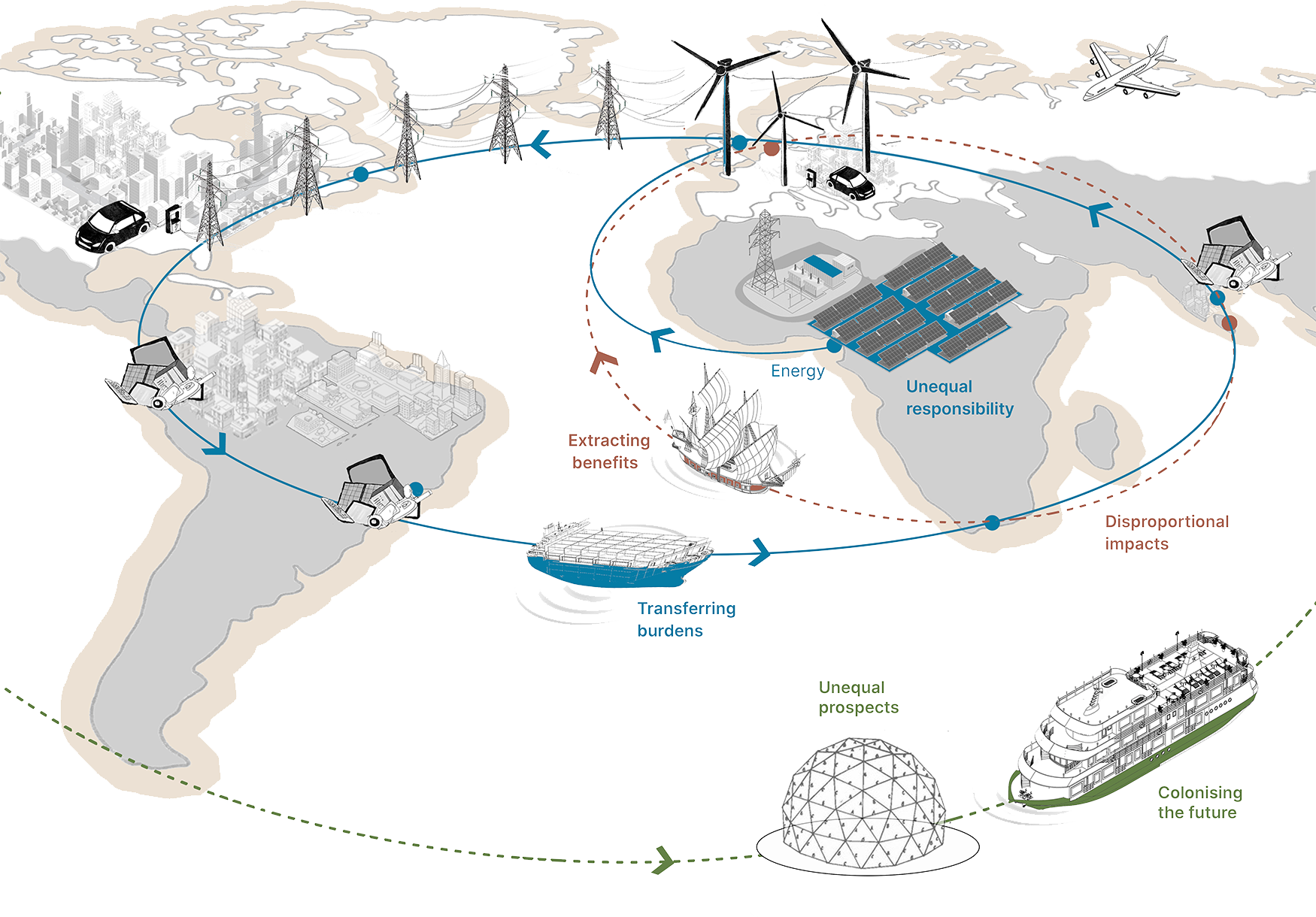

To follow the principles within the visuals, sectional and isometric perspectives were deliberately employed rather than traditional top-down or plan views. This helped to present the inner workings of physical and human infrastructure which are usually concealed. One influence for this was the “Ship of Theseus” paradox, to interrogate whether selective and surface level changes towards climate action suffice or whether a radical reconceptualisation of efforts is required. Through successive discussions, the visuals were refined to illustrate that superficial retrofits within city policies rely largely on an underlying (neo)colonial and capitalist framework without addressing historic injustices at their root.

The visual narrative was produced through an iterative, dialogic process based on the three authors’ transdisciplinary perspectives. The aim was to integrate insights from the paper with imaginative modes of understanding. As Roes (2017) note, artistic interventions in research can facilitate a dialogue with someone who does not share the same lived space but is able to engage visually. To do this, an accessible visual grammar was incrementally and exploratively developed. This required taking into account how the different compositional elements would come together in the series of visuals to develop the concepts, gradually breaking down their complexity.

Initial sketches were collaboratively refined to challenge universalised representations. For instance, the normative Eurocentric cartographic projection was done away with, as it was antithetical to the paper’s decolonial stance. Instead, a South centered map was adopted so as to foreground colonial histories, extraction zones, and possible alternative futures.

In adopting alternative forms of narratives and artistic transdisciplinary knowledge-production, the entire process from deliberation to the final images demonstrates that collaborative visual praxis can meaningfully supplement analytical research and foster engagement beyond the academic spheres.