Role

Summer School Participant

Organised by

IIHS, Utrecht University, Freiburg University, Stellenbosch University, ALU, Freiburg

Year

2023

In this last week of March, I attended a Summer School organised by the ReSET consortium at IIHS. It has been two and a half days of a lot of questions and as always too few answers. However, to be fair some of these questions are also new to me since I have only now placed my inquiries within the energy transitions domain. I haven’t previously documented questions and thoughts from academic interactions on my blog. But with this, I hope to initiate a personal effort to find firm ground for the fleeting yet fervent ideas that arise in such interdisciplinary gatherings.

On the first day, in the first hour, eleven of us that formed the summer school cohort (nine doctoral candidates and two lone doctoral aspirants / practitioners), were tasked with creating an energy timeline for India. Now, this isn’t new. It has been traced in academic research, policy documents and in media as well. However, bringing together all the different energy sources, policies, key events, social movements, global issues on one timeline was and is always a hard task. What makes it to the limited space on the floor and what remains left out?

Mind you, this is our introduction to each other as well, since we all come from different fields of practice, knowledge levels and academic backgrounds. So, it was an impromptu discussion on what were the crucial moments in shaping the energy narrative in the country. A lot was left out on the floor, but a lot was gained, in terms of understanding each other’s entry point to this conference and energy research.

I have put together a digital version of our sticky note timeline below for those that are interested to learn about unseemingly connected events in our energy history.

How can we radicalise energy politics?

We all live in an energy insecure world. That much is established. Which is why there is an appeal of energy security within the renewables.

Politics of coal: Welfarism

Politics of oil: Neo-liberalism

What is the politics of renewables?

Renewables have a decentralised nature, it really depends on how we plan for its operations, governance and holistically for the transition. Prof. Mark Swilling from the Centre for Sustainability Transitions at Stellenbosch University very succinctly put across the various positions on just transitions:

Position 1: Renewables promise economic growth and more jobs.

Position 2: More jobs for a very skilled group of people, but there has to be welfare provided for those that are going to be negatively impacted

Position 3: (From trade unions) Renewables have the power to transcend capitalism and move towards a socialist world.

Bruno Latour’s inquiries of what is the agency of material objects in this domain, echoed through everything that was being said.

The most subversive thought within this summer school for me, was: Are the increase in renewables really contributing to decarbonisation? If it isn’t the clean energy that is is being made out to be, what are we transitioning for? This rang true especially in the case of Pavagada which was a case study for us and a context to ideate potential just futures.

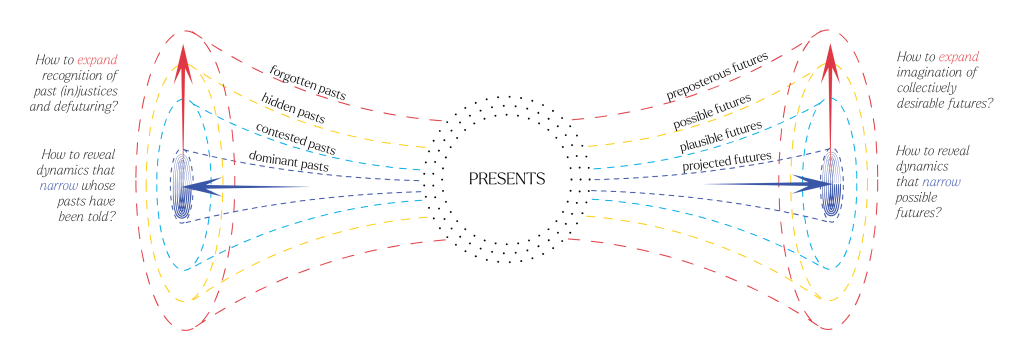

Prof. Maarten Hajer had an interesting presentation on dramaturgy and the performance of governance. He spoke about the way every one wanting to create change is essentially performing to ensure it is realised. For example island nations having a climate discussion underwater to appeal to the rest of the world that they are mere years away from losing their land to sea level rise. Even in the political discourse, one has to carefully watch out for the dramaturgies playing out. After all – all the world’s a stage. He also spoke about futuring, which is an interesting way of building consensus – imagining scenarios for the future. However, being able to do this comes with great privilege and each of us needs to be very clear of our positionalities. India, for instance doesn’t have the luxury of futuring as compared to say, the Netherlands. And as Prof. Mark Swilling exclaimed what the Global South does have is the evolutionary potential of the present.

What is the proportion of energy poverty in India?

This was the big question that was asked multiple times across the summer school. It is a nebulous term since there is no one unified definition of energy poverty and more so one that is contextualised to a country like India. It is understood that the definition will have multiple layers and dimensions to it. What there are, is yet to materialise collectively.

Poverty is increasingly understood as the deprivation of opportunities for living a dignified and good life (Bhide & Monroy, 2011). What a dignified and good life is a whole other debate, which also arose multiple times during the summer school. In this sense, “energy poverty is defined as the level of energy consumption among households living below the poverty line (BPL)” (Foster, Tre, & Wodon, 2000)

Does this mean then that households and communities that are economically poor are also energy poor?

Mega-projects for social justice?

Case of Pavagada, Karnataka, India

The global energy transition from fossil to renewable energy is gaining momentum and coming to scale. The scaling is largely driven by mega projects: large scale and complex undertakings (ReSET Team). The Pavagada Solar Park, operational since 2019, is at this very moment, the third largest solar park in the world covering around 53 square kilometres. It is working at the capacity of producing 2050 MW of energy and an additional 300MW is in the pipelines, to be operationalised by 2026.

The interesting model here is that the farmers in the Taluk have not sold their land, they have given it on a 28 year lease to the Karnataka Solar Power Development Cooperation Limited (KSPDCL) for an annual revenue of Rs. 21,000 per acre which will increase by 5% biannually.

In 2023, journalists Pragathi and Flavia wrote an incisive piece funded by the Pulitzer centre on what this means for justice in the energy transitions for the villages in Pavagada and the renewable energy goals in India. The illustrations used here were made by me to support their reportage.

The residents of Pavagada and lessors of the land do not get their electricity from this solar plant. The energy is fed into the grid that goes to the cities. How can we start thinking about a socially just way of developing a mega project such as this? There are social, economic, technological, political, ecological and financial implications when imagining any mega project, but what possible energy futures can we imagine for the Pavagada Taluk?

We presented some realistic visions and some radical visions and all in between. This connected to the earlier thoughts on

how can we radicalise energy politics and also situate it temporally?

Community is a social construct and it isn’t a homogeneous group that exists out there. A community is built and community building can be facilitated in cases such as Pavagada. The crux of it is to identify a common vision for people to collectivise. At the heart of it, each individual landowner and worker have competing sets of values, but the unseen commonalities have to be revealed. For example, the valuation of the land is made based on what the productivity of it was. For a moment, let’s comprehend how much money it would mean if the valuation of the land is made based on what the productivity of the land is considering it is providing 2050 MW of energy to cities. It is crucial to expose contradictions between values just as it is to reveal mutual benefits. People will always collectivise around wanting to know more, around being curious at what could be as opposed to what is. Can we embed rights for the land, like the river in New Zealand became entitled to rights, like an individual is.

To the lands degraded,

by the promise

and potential of the sun,

I see you.

To the plants,

in the dark,

under the panel that powers my house,

I feel you.

To the energy,

that flows into grids,

and guides political narratives

I hear you.

Loudly.

In the lines outside my window,

where birds refuse to sit.

Organising team:

Megan Davies, Centre for Sustainability Transitions, Stellenbosch University

Mark Swilling, Centre for Sustainability Transitions, Stellenbosch University

Philipp Späth, ALU, Freiburg

Mithlesh Verma, Indian Institute for Human Settlements

Stuti Haldar, Indian Institute for Human Settlements

Amir Bazaz, Indian Institute for Human Settlements

Aromar Revi, Indian Institute for Human Settlements

Jesse Hoffman, Urban Futures Studio, Utrecht University

Maarten Hajer, Urban Futures Studio, Utrecht University

Cohort:

Sukanya Khar

Thandeka Tshabalala

Sneha Swami

Sobhagya Mittal

Rudeena Jabar

Rohit Patwardhan

Priyank Jain

Pranusha Kulkarni

Kevin Foster

Azam Danish