Role

Qualitative field research

Collaborators

Indian Institute for Human settlements (IIHS)

Year

2022

Introduction to the project

The research was led by a consortium including experts in urban research from Africa and Asia, brought together by the Institute of Development Studies. This project was a part of my fellowship programme at the Indian Institute for Human settlements, Bangalore in 2022 wherein I was involved in the preliminary analysis of water infrastructure. The project concluded in 2023.

The focus was on five main types of infrastructure – water, sanitation, energy, transport and communications. In most poor neighbourhoods people meet their needs in a variety of ways – informal access to formal grids such as illegal energy hook ups; ‘off-grid’ forms such as latrines or bore-wells; hybrid forms such as reliance on water trucks when urban supplies run dry; or local vehicles providing ‘last-mile’ connections to public transport. A particular concern in these cities is whether such critical infrastructure is sufficiently robust and stable to weather the multitude of human/political and environmental shocks and stresses facing cities.

The project takes a close look at infrastructure assemblages which refers to not only the multiple arrangements of physical infrastructure but also the socio-political relationships and relationalities between the components. The site chosen for this research is Kadugondanahalli which is located in the North-east of Bangalore in the vicinity of Frazer town. It is also known as the ward with maximum non-revenue water.

The aim of the project was to connect it to larger understanding of food retail and consumption within the ward after a study of all the resource infrastructures available.

Methodology

This research was conducted at a ward level (Ward #30 – KG Halli) with both primary and secondary research methods.

Secondary research

Field visits: The methodological approach to the primary research at the site has been qualitative. Qualitative approaches helped uncover concerns of exclusion, disruption, changes, repair and resilience.

– Notes from field

– Photo documentation: We conducted structured field observations, walking-mapping exercises and semi-structured interviews to understand infrastructure availability and food systems in the neighbourhood.

– Key person interviews: We conducted semi-structured interviews with local leaders, administrators and influential people of the neighbourhood in order to map the history of the neighbourhood, understand the infrastructure and their daily lives.

Building a framework to understand practices, actors, provisioning and ownership across typologies. We transcribed, coded and analysed the information gathered.

Visualising the data for the community and the authorities

Areas of research inquiry

Throughout my field visits, I kept a record of all our observations:

We started out at KG Halli Community Health centre at around 3.15 PM. We walked towards the BBMP office and tank to the north and took a turn to the left on Mariyamma Temple street. We came across a water ATM that was shut at the time. This is one of the water ATMs in the ward.

While on the way to Pillana garden, we noticed a well with water in it although it was quite polluted. There was a tank right next to it with a tap, maybe this was the supply? The materiality of these pipes and connections were quite interesting. In some places, due to or breaking of the BBMP installed plastic pipes and taps, the connections were replaced by metal ones. Mostly though it was all black plastic pipes. Some homes had illegally installed borewells within their compounds. We do not know how metering works in such cases, how are all these accounted for?

What are Grid and Off-Grid systems?

A grid is a formal system that is under the control of a centralized governing unit; in simpler terms any underground / overground service delivery network like the Kaveri pipeline or electricity lines.

Off-grid systems stem from different arrangements for provisioning of services with an involvement of a variety of actors. On closer study, off-grid arrangements are not devoid of defined systems, processes, pricing logics and often involve both human and non-human entities. It is important to understand that grid and off- grid arrangements cannot be equated with the binaries of formal and informal or state and non-state systems. Another thing to note is that technical structures such as grids are not apolitical in nature. They are constantly disputed.

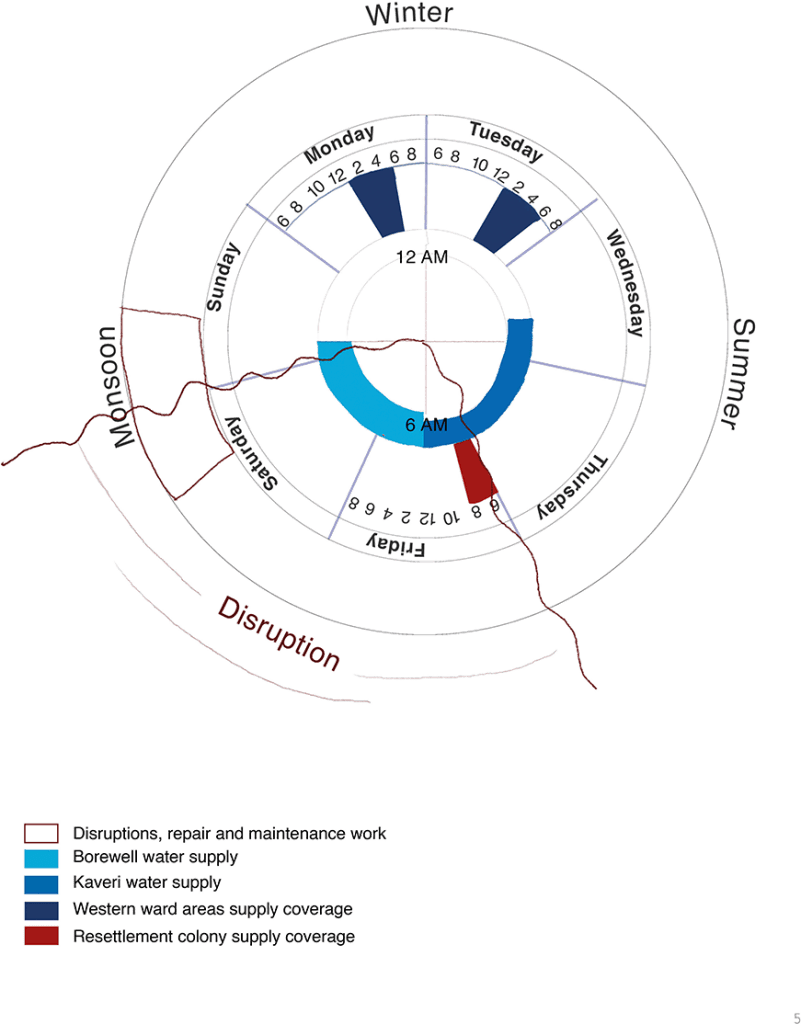

Disruptions, cycles of crises resolved through negotiations and protests, make this process more cyclical than linear. Water supply, maintenance and repair schedules were further mapped to analyse the temporality of these systems.

Social and spatial aspects

A major part of the ward features as neighbourhood type-3, that is, low socio-economic status. Which means, it consists of dense neighbourhoods with small plot size, high-street density, unplanned and unorganised street layout, minimal vegetation, and high built-up density.

There is a wide range of spatial variations in terms of accessibility of infrastructure as we move from the western to the eastern sections of the ward. There is also variation in terms of the neighbourhood typology while moving from northern to the southern part of the ward. The southern part of the ward is called Pillana Gardens, and is known to be an affluent neighbourhood in Bengaluru. There is also a slum resettlement colony that is situated in the centre of the ward.

The ward has largely been constructed by its own residents. Bhavani came to KG Halli 25 years ago and bought her own house by a tiny galli 15 years ago. However it was only 10 years ago that the sanitary lines and water lines were installed. These too, were incremental – happened only because the resident from the streets collectivized and approached the councillor many times.

Delivery and materiality of infrastructure

Water ATM

5 ATMs located across the ward. They are used when Kaveri or Borewell supply is disrupted. They supply RO treated bore water. These water ATMs are positioned by political and civil society actors, with support from the state for provisioning of water. The flexible placement of water ATMs as extensions of networked infrastructure or as completely independent, has led to its distinct categorisation of that of ‘pop-up infrastructure’

Water Tankers

Water tankers are used to supplement Kaveri and borewell supply.They are accessed only during the disruption of primary sources. They cannot access narrow lanes of the north and east highly dense areas. There are multiple actors involved, residents call upon not just BWSSB or BBMP tanker but also private contractors to deliver water. The source of the private tankers is questionable.

Borewell connections

Borewell water supply and use increases from the west to the low lying eastern areas of the ward. Across the ward, borewell is dominantly used for washing and cleaning. However, in the eastern areas or when there is short supply of ‘sweet’ Kaveri water, people resort to using the borewell water after purification for drinking and cooking as well. The location of the community borewell standposts were decided after the houses and residents settled in the neighbourhood.

- Water is supplied from the main reservoir to the different areas within the ward through a system of valves. Valves control parts of the larger grid to provide supply of bore-water through bore-pipelines in the neighbourhood.

- The electricity to control the flow and pressure in the valves comes from these panels. These valves are maintained by the bore valve-men, and the functioning of valves is very similar to that of Kaveri valves.

- The major difference here is that bore valve-men are not provided with any schedule from the governing authority. The schedule for who gets water first and who doesn’t is a socially evolved practice depending on time, space and relations.

Kaveri connection

Kaveri is provided only by BWSSB. The Kaveri water is pumped from the Ground Level Reservoirs (or GLR). They are usually situated in the higher elevation. Kaveri water is pumped from these GLRs. The closest GLR in ward 30 is Machalibetta GLR and this is situated 2 kms away. Motors are a dominant mode of collecting Kaveri water.

Mapping supply schedules: Temporality

It was challenging to capture all of the contradictions and layers when it came to schedules and repair and maintenance cycles. The disruptions described were of varying reasons starting from Padayaatra for Mekedatu dam all the way to contamination at the source. Just to get a brief idea, I put some of the information together in a diagram. This is also an intersection of the human and non human actors, starting with the time schedules in itself to why there is a disruption. For example, for two hours every few weeks, the power is switched off in the neighbourhood so that no one can use their motors and even the low lying areas can access Kaveri water. It is very hard to capture such nuances in a linear sort of diagram.

The water infrastructure is a combination of networked infrastructure. It is deficient in varying degrees but there is an attempt to offer rational service – whether individual or collective/ formal or informal

Read the other project outcomes here.