Role

Qualitative research

Collaborators

Jayavartheni Krishnakumar, IIHS

Year

2021-2022

Introduction and methodology

This project was initiated as part of a field research component in my fellowship at Indian Institute for Human Settlements, Bangalore in 2021. This research took many forms, starting with an ethnographic study presentation, to a short film which was generously supported by the Bangalore International Centre in 2023.

We spent four months in various parts of the city but majorly speaking to people residing in and around a highly dense and marginalised neighbourhood in the northern part of Bangalore. Following is an outline of our field research

- Inquiries into a practice rooted in place

- Cycling as a tool to understand leisure

- Space as enabler to the practice

- Spaces observed: Streets, parks, playgrounds

Bangalore, amongst other things is also known to be a cyclist’s haven partly due to its favourable weather and abundant tree cover. However, like many other cities in India, the infrastructure in place isn’t friendly to cyclists. Despite this, there is no dearth of efforts from citizens and civil society organizations to make themselves and their needs visible, which made us root our inquiry here. There are formal open cycle days, car-free Sundays and Cyclathons organised by resident welfare associations and private organizations, that have gained significant traction over the years and have become a part of the city’s cultural fabric.

Our research seeks to inquire the sites of cycling practices and informal modes of collectivisation that miss the mainstream attention. These informal acts sustain the act of cycling by bringing together communities passionate about it, but are seldom seen as a deliberate attempt towards climate or environmental activism, unlike their elite counterparts. Bengaluru has no specific guidelines or an overarching administrative apparatus that regulates cycling. What we do know is that cyclists are clearly a big part of the city’s everyday. But who counts as one, people who cycle for leisure, ones who cycle to reach a destination, or people whose workplace is their cycle?

How can we make space for all kinds of cyclists who inhabit our city?

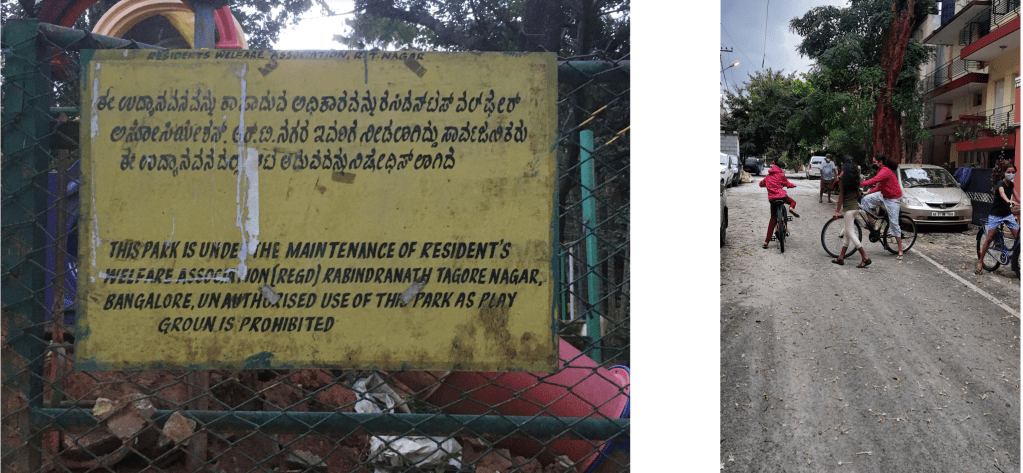

There are a number of municipal parks and playgrounds, the conceived spaces of leisure, that are rendered inaccessible spatially, socially and economically. On the other hand, streets are common sites of social interactions and hold different practices of leisure, of people across different generations.

Research Question: How do leisure practices shape the way people interact with place?

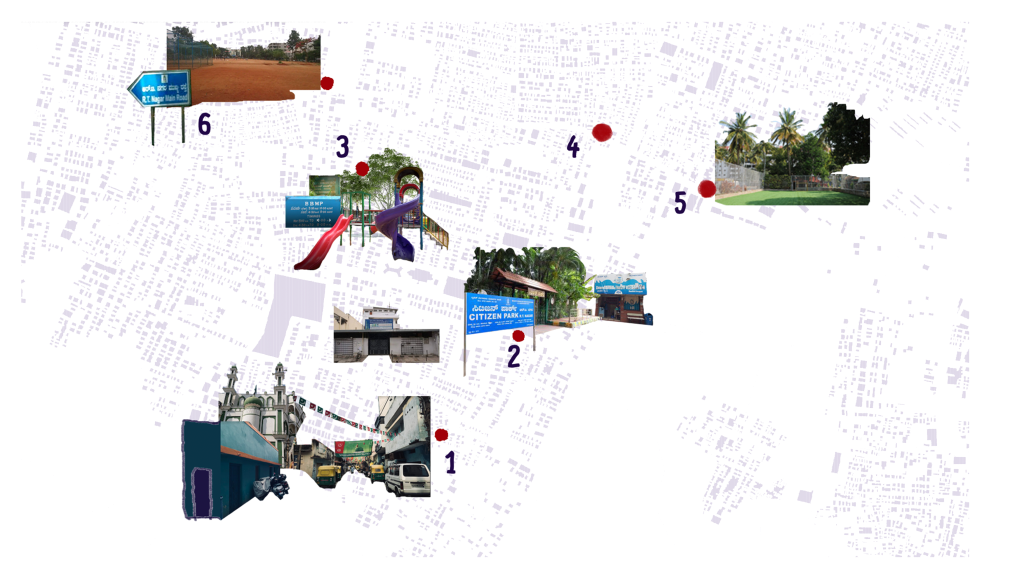

This project started with walking around RT Nagar, Bangalore to find sites that produce leisure, facilitate social interactions and sites that correspond to the consumption of leisure. We began by following the naala, a strong geographical feature, that we observed to be creating social multiplicities. Although the naala didn’t provide us what we were searching for, it led us to a cycle moving swiftly down a steep slope. With great difficulty we managed to follow the little boy up the incline and emerged near a Madrasa.

Spatiality

The roads are narrow, winding, peppered by towering mosques, the azaan blaring through the streets, carried through winds much cooler than the area we had left behind. Tightly packed residences stacked above one another spilled onto the street. Homes were punctuated by spaces of commerce. You could catch strings of sentences being uttered in Dakhani. Rhythms, they reveal and hide.

The residential streets felt like walking through a series of living-rooms. The main streets stretching out of the Bilal Masjid constitute commerce based on manual skills like metal-crafting, sewing, two-wheeler repair. The people are sitting on their compound walls or on the gate engaging in small conversations with the passers by who in-turn are negotiating their way through the streets, indifferent to the wheelers.

Cycle’s cycle

The kids in the neighbourhood have cycles bought second hand from the KR Sunday Market and as these kids grow old the same cycles are sold to other neighbourhood kids or their wheeling companions. Abbas & Sons run a repair shop that gives a facelift to these run down cycles. The kids are enterprising, quick at market rates and know the markets where they could source the spare parts from. They have their way into the black markets of the city, which helps them procure cycles at cheap rates and sell them back when they need a change. The kids say “no cycle that comes here goes to the trash”. The practice of leisure here has made this community a part of a circular economy and sustains itself through this cyclical exchange.

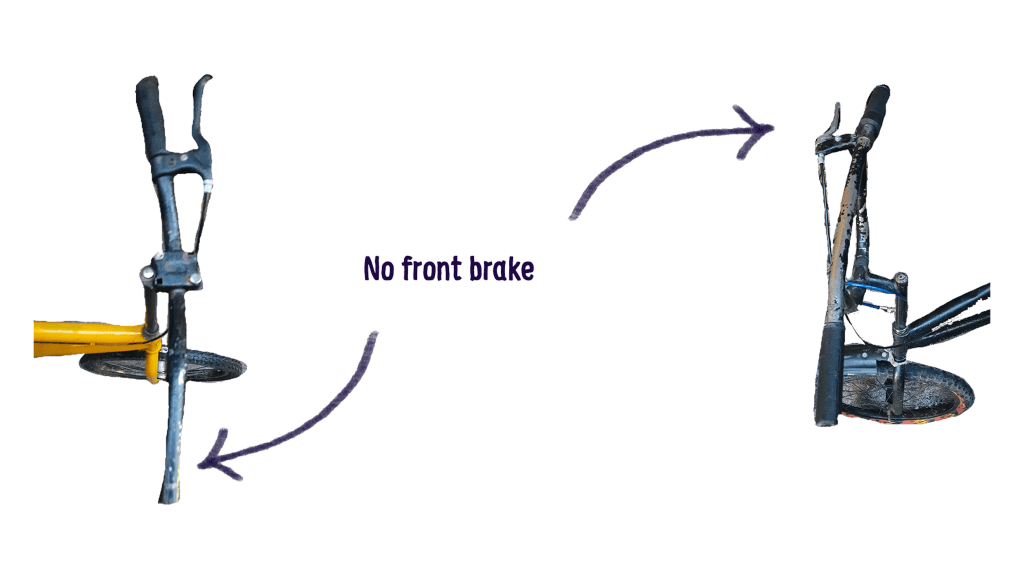

There exists in the cycling tradition in this neighbourhood, an implicit social hierarchy. Only a select few had the honour of attaching the suffix wheeler to their names. Their status was also evident by their handlebars, which had no front-brake. Though all of them were 13-14 years old, their cycling skills put them at a position where they could bully an adult who couldn’t wheel. “It takes 3 to 4 years to learn how to do a wheelie properly.”

They explained how a bumpah on the road helps them lift the cycle-front and how the upward slopes helped them hone their wheeling skills. This young community of wheelers and almost-wheelers comes in its full form on the ‘Shaaban’– the month before Ramzaan. Around 100-150 cyclists gather on the Jakur Road or Nice Road or Tumkur Road post the last namaz of the day to manifest a collective identity of wheelers. And if you challenge someone with a better cycle and win, the cycle belongs to you.

Surveillance

Risk is ever-present in this neighbourhood’s small, bumpy roads, but the one thing that terrifies young cyclists the most is the police. At Citizen Park, Rehman abruptly puts his cycle down and turns back, wary of the police van circling the neighbourhood. Here, the boys tease each other with a tinge of caution in their tone – be careful, or the police might come for you. Though the police can’t really fine cyclists for not following rules on the road, one can only wonder why the young boys fear law enforcement so much. When asked about the police, they recall their experience when the policemen took them along with their cycles to the police and the parents had to pay Rs. 4000 bribe for their freedom. Perception of surveillance by family/community is different from perception of surveillance by authority. Active resistance in the form of cycling against communal policing and actual policing feeds their collective identity.

Here we see how the process of becoming a wheeler, highlights the emergent nature of leisure which is greater than the sum of their singular experiences. This community of wheelers, in their acts of resistance come together to manifest a collective identity and in turn social behaviour.

Girls don’t do wheelies; girls stay away from the main road; girls quit cycling soon because of surveillance, parents, studies, superstition or even the more sophisticated freedoms of a two wheeler. As girls grow up, their bodies are surveilled further and their interests are directed towards activities more suited to the indoors, you only need to look at the walls outside schools in RT Nagar lined with photos of girls who top their board exams. Maybe the girls aren’t allowed out on the main road to cycle because it is dangerous, but maybe they’re only allowed outside the streets near their home because their parents and neighbours prefer to keep a watchful eye on them? And how do you expect them to pick up wheelies with the boys, when the pinks and purples of their cycles are the first sign of a growing divide?

Gendered marketing

Cycling is gendered – this much is obvious. Women are slowly moving away from cycling, or at least, double-checking their apparel, the times they cycle, and the areas they cycle in within Bangalore (according to several reports and research). It is possible that the girls are slowly moving into a context where their bodies are being surveilled because of their gender, or it is also possible that their surveillance is marked by the fact that they are still children. These are questions for another time. For now, revel in the stories of three girls who love spending time on cycles. Because, girls who do cycle for whatever little amount of time, hold their time on two wheels close to their hearts.

We started out asking ourselves how leisure practices shape the way people interact with place. It is evident that people adapt to and master their place when indulging in the practice of cycling, with an intimate spatial and temporal knowledge. We understood however transactional a place is conceived to be, undesigned features like slopes make for a liminal place of leisure. We saw that riders didn’t just merely interact with place, they conquered it, making the place adapt to their practice of wheeling. Although, we know that the non-cyclists aren’t too happy with this conquest – with some throwing cold looks at the “stunts” performed on the streets. In an auto-centric city, is cycling an act of resistance in itself?

It is important to add that these spatial interactions are scaffolded by social and economic practices, some roads are far too hard to conquer, with the main road being a lane few riders traverse with ease, particularly inaccessible to girl children. The intersections become evident, how being spatial restrictions for women, invisibilizes them socially and in turn makes them economically vulnerable. Finally, we know that these joys are not easily available to girl children who cycle and if they do, their time on two wheels is numbered until socio-cultural constructs lead them away.

Who is a cyclist?

Cycling identities

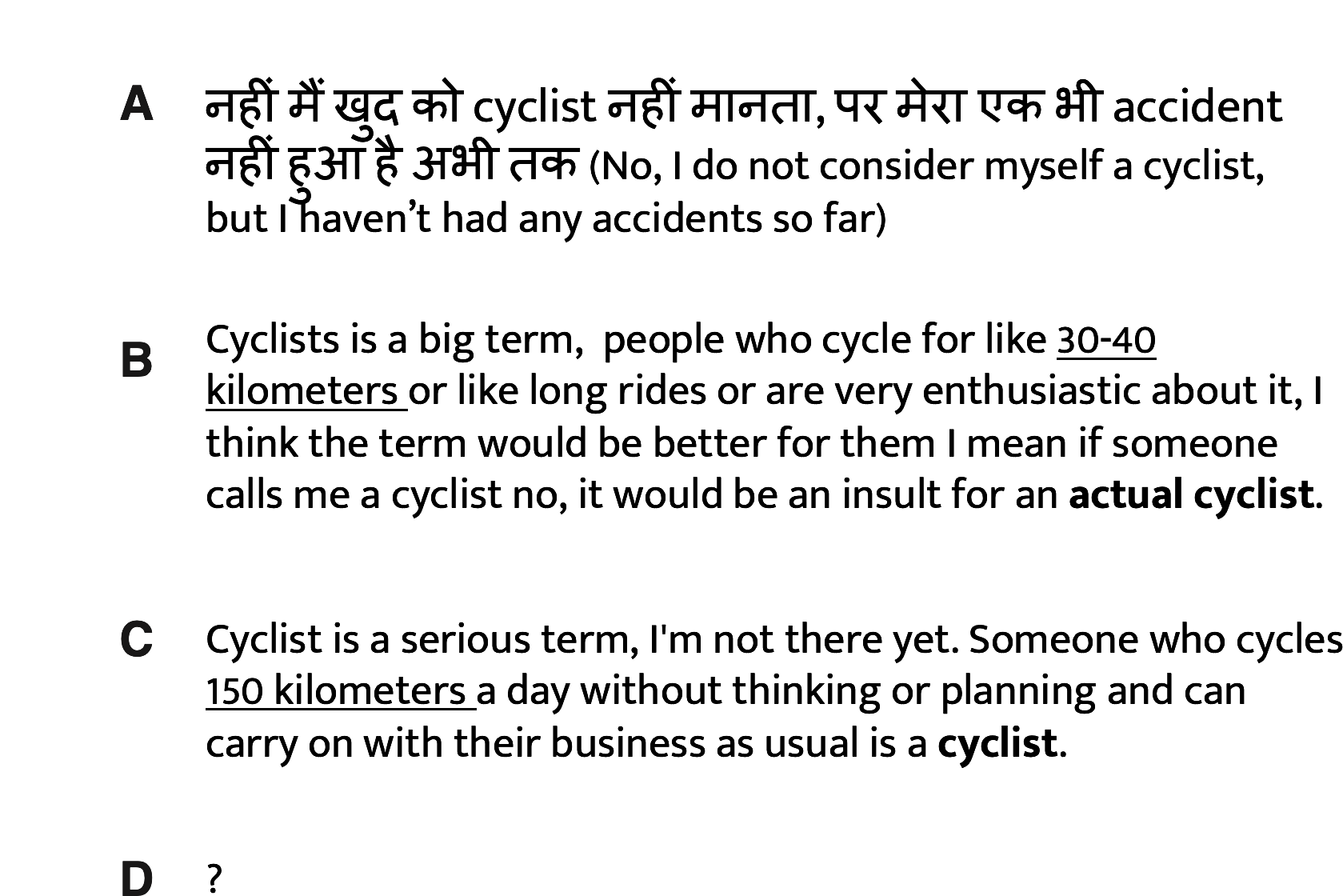

This brings us to the question: Who is a cyclist? From the field – we tried to understand the criteria one has to satisfy to be a ‘cyclist’ along with the diversity of intentions and motivations behind their cycling practices. When we asked our respondents if they consider themselves cyclists, we saw the baseline criteria of a cyclist to be shifting in different user groups; The language imparts obscurity and sense that people consider being a cyclist to be unattainable.

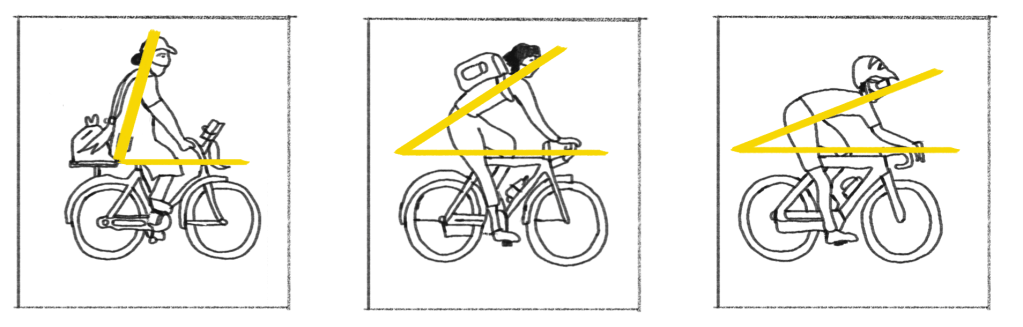

The standard seemed to be scaling up on the basis of a person’s motivation and aspiration towards cycling. It ranges from — the tacit skill of riding safely on the roads, motivation of picking up cycle just for the fun of it, investing in gears/equipment to sustain the practice all the way to committing to cycling distances as long as 100-150kms and being able to go about their day with no exhaustion.

What’s funny is, the more the angle of inclination, the more likely you’re identified to be an actual cyclist.

Livelihood cycling – the practice of carrying out a business from cycle or using cycle. This includes newspaper distributors, post – men & women, fruit and flower vendors.

Commute cycling – the practice of cycling to commute. The motivation includes but is not limited to work trips and short errands.

Serious Leisure – a systematic pursuit of cycling, involving skill and endurance. The motivation ranges from fitness, enjoyment and environmentalism, this requires a certain degree of commitment which differentiates it from a leisure practice.

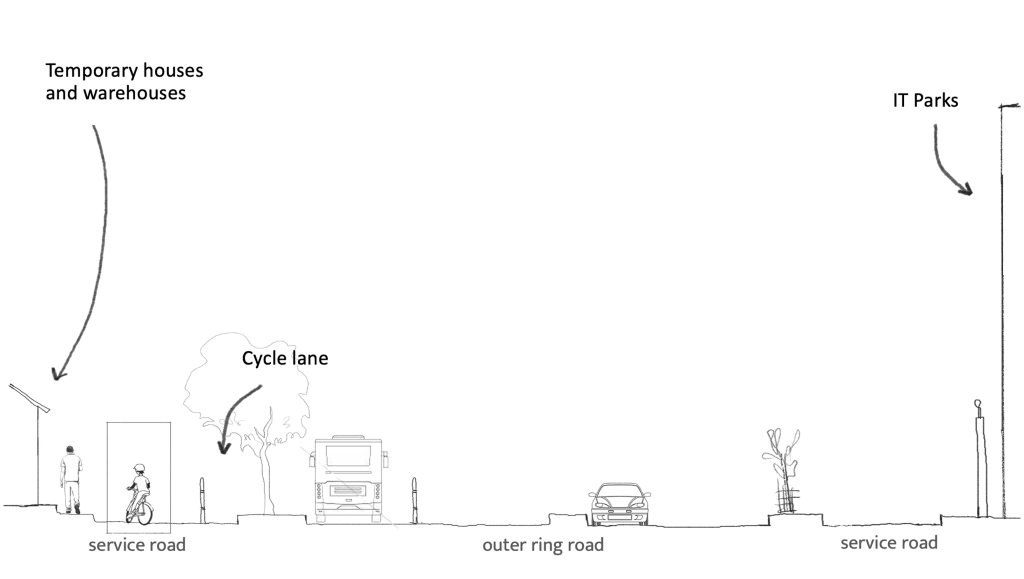

The outer ring road is flanked by the glass paned grade-A office buildings on one side which a lot of riders seem to identify with and on the other side – garages and temporary houses which inhabited the construction workers, security guards and other ancillary service providers. Though a lot of people from the settlement cycle to work, none of them prefer to ride on the designated cycle path.

Spatiality

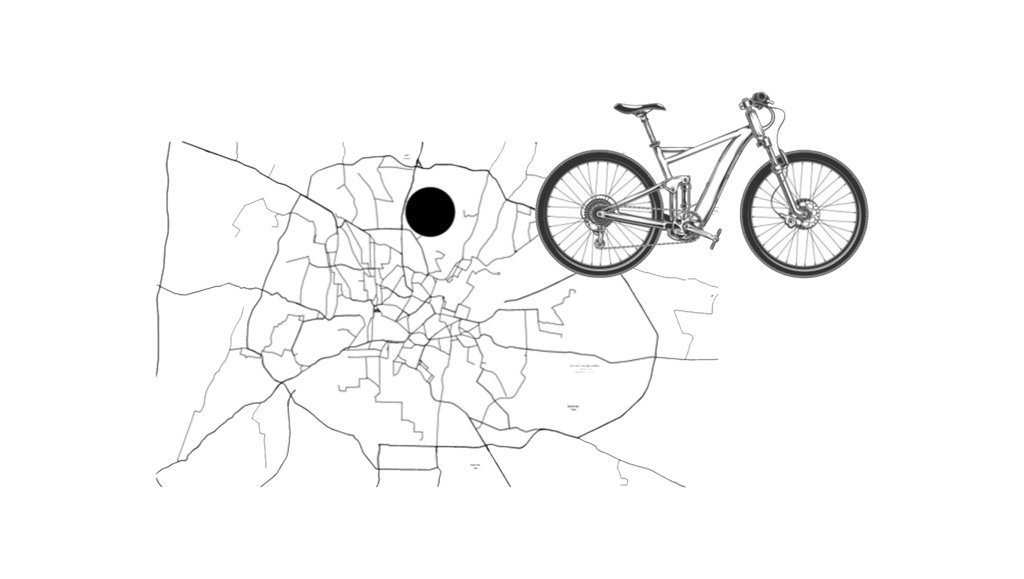

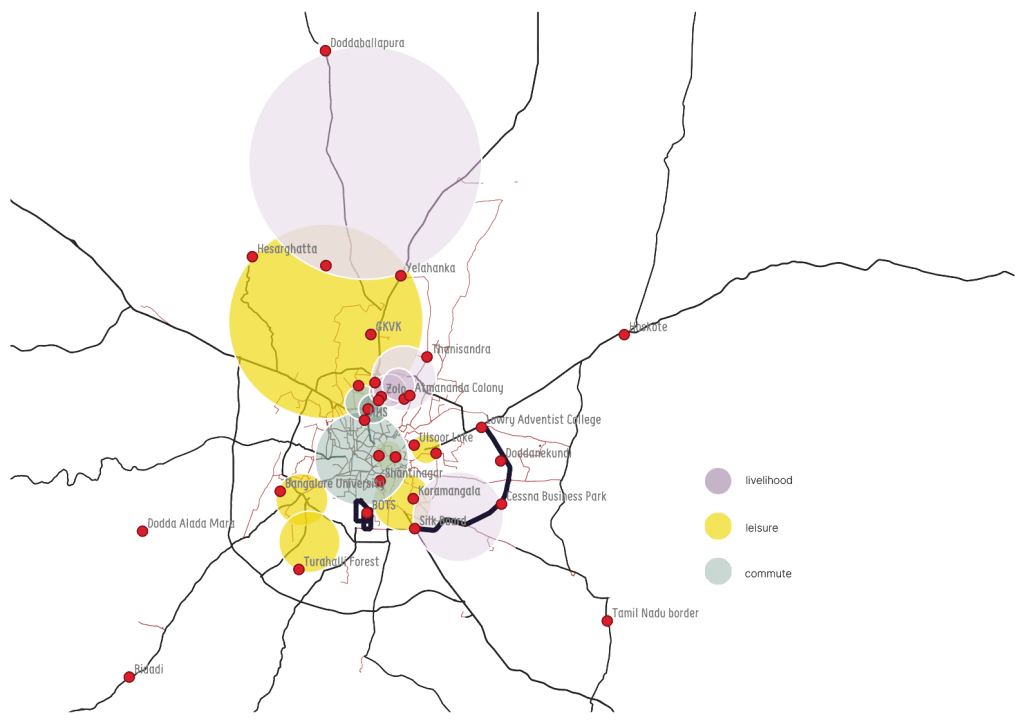

We tried to map the extent to which these different cycling practices are spread – along with the cycling infrastructure that are in place to see if there’s an overlap. Our sample had an equal ratio of the three practitioners. Within our respondents the livelihood cyclists seem to venture the furthest, around Outer Ring road, Yelahanka, RT Nagar, Thanisandra. They’re followed by leisure cyclists – owing to the specificity of destination or the route itself like – Hesergatta, GKVK, Avalahalli forest, Cubbon park, Ulsoor lake and Turahalli. Last, commute cyclists cover specific routes in Sadashiva Nagar, Mekhri circle, Jaya Nagar and MG road. The location of cycle lanes do not majorly intersect with the routes of our respondents here. Locating the different practises and overlapping them with the mapping of time showed us that livelihood cyclists cover the largest extent and spend the longest time on the roads.

Situating commute cycling in the intersection of livelihood and serious leisure practices makes sense, as the motivation behind the choice of commute ranged – from experiential, economic, environmental, fitness & wellbeing – pushing them to choose cycle over personal automobile. Here, we try to understand how parallel identities are formed around cycling and when it stops being just an activity. Why does a newspaper distributor not identify themselves as a cyclist? Does this understanding influence the way they relate to the city?

Few reasons for motivation cited by our respondents suggest that using a cycle is associated with cost-saving benefits and in turn perceived by leisure cyclists as a practice of the deprived. We look to understand how these identities are formed and reproduced on larger scales – in communities, resulting in the marginalisation of livelihood cyclists. The identities of commute and serious leisure are largely formed by distinguishing themselves from the livelihood cyclists by attributing their practises to being eco-friendly or fitness-related discourses. This vocabulary translates into material aspects via symbols like “Go green!” on T-shirts and also with marketing strategies that cite physical well-being and social desirability in their branding.

Collectivisation

Cycling is as much a practice of community as it is a personal experience, it provides for a collective voice against the hegemony of motorists on roads. They provide two critical functions – first by identifying as a part of the community they adopt and display shared symbols to propagate discourses that legitimise the practice of cycling by making it an ethical discourse for larger public good. An offshoot of Bengaluru Bicycle club called ‘Go green go cycling’ club induces people into the practice by organising beginner rides for IT sector employees – mobilising for initiatives like Cycle to office.

The second function is of building a community that enables knowledge transfer, skill-building and social learning. DULT along with Jhatkaa and pedal in tandem organises cycle school for women with an approach of teaching women how to use a range of cycles including geared ones and upgrading their technical skills like fixing tyres and maintaining cycles. This plays a critical role in building a practice from scratch, allowing experimentation and stabilisation. There are a number of online groups that serve this function by building repositories of shared knowledge on bicycle gears and accessories, routes within and outside cities and technical know-hows of safety and maintenance. These forums are not just limited to online participation, they extend to offline activities too. Bangalore bicycle club is one such forum along with RACF – Ride a bicycle foundation- that successfully lobbied BBMP to commission bicycle lanes in Jayanagar.

And what of the women? There’s a mother, whose face falls whenever she thinks of how she wasn’t allowed to cycle. There’s a flower seller with her stationary cycle — only her husband’s allowed to drive it. There’s a regular cyclist who dresses not to cycle, but to ensure she’s not perceived. From leisure to serious cycling to livelihood cycling, women’s aspirations extend across the spectrum, their desires ranging from safer roads to more agency in the workplace to simply learning to cycle.

Among major reasons such as safety, cycling also influences the choice of clothing for women, sometimes impacting their confidence on roads. This in turn feeds into the women’s choice of routes based on visibility – translating to a form of surveillance and if something goes wrong – a means of redressal. This reflects in the time women hit the roads, majorly limiting themselves to mornings due to lighting and the less density of traffic. The support function of active women cyclist groups fills this gap when they come together on commute and recreation – enabling them to explore new places, also giving them a choice of timing rides to their convenience.

The key to solving problems comes down to this – we know who cares about what, but how do we make one person care about what the other person wants, alongside what they want. Making mobility, leisure, and access universal isn’t solvable by a group of people agreeing upon a few common terms of action – the terms we talk about are spread too thin, often with no intersections. This needs a different approach.

How can intersectional identities around occupation and mobility come together to mobilise for better infrastructure? Recognising their unique occupational needs, how can this be done without homogenising their occupational identity?

Perception of cyclist identities translates into access spatially and politically – whose urban imagination feeds into policies? The pace of livelihood cyclists is determined by their occupation and the kind of goods the service entails. If a 3ft cycle lane is designated for the cyclists – who would get a right of way? A serious leisure cyclist who’s riding on the 21st gear, or the scrap dealer carrying a bundle of newspaper on the carrier and bag on the handlebar?