Role

Artistic Research and storytelling

Collaborators

Kadambari Komandur, Megha Kashyap, Bengaluru Sustainability Forum, Paani.Earth, WASI

Year

2023-2025

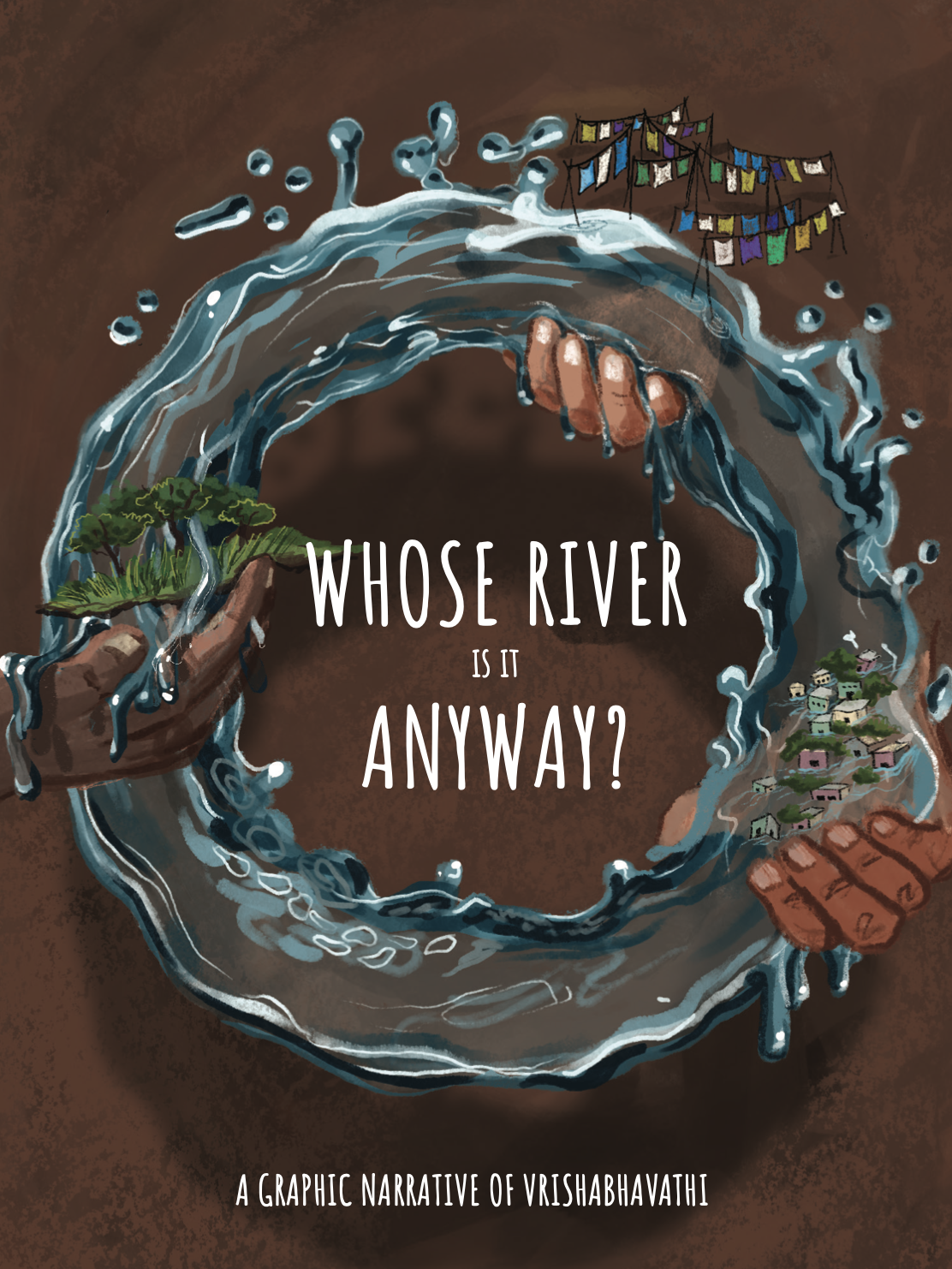

Whose river is it anyway is a collaborative endeavour presented in the form of a graphic collection of stories of an urban river. The book grew from an imagination of the river as an independent being, flowing with agency and with a voice of her own. During the peak of the first COVID wave, in July 2020, we came across an article in the Times of India, with a picture of a relatively clean Vrishabhavathi river. This was a period when the industries in Peenya were not functioning and therefore, not discharging effluents. Our project unbeknownstto us actually began at this point, as a personal journey of understanding what we back then, as young architects, and citizen scientists could do to raise awareness about the river.

This book is an exercise in countering the dominant representation of rivers being state owned and human-controlled which creates an illusion that if we humans build enough infrastructure, we can conquer the river and break her natural state of being. While the Vrishabhavathi seems to be a river known to only a few in the present day, parallels can be drawn to other urban tributaries that have been relegated to misuse and disuse, marginalising people and dependent biodiversity. We hope that this document will counter this narrative and give a stronger voice to urban waters, by seeing them through eyes that are not just our own – those of beings in these bodies, animals dependent on them to quench their thirst, plants living and dying with their flow and of course the water through her own experiences of being.

Through constant iterations, we debate how to present and represent a river, considering the limitations and flaws of data-focussed satellite based techniques. We sought to document what bottom up approaches to mapping could look like and in that process initiated exercises in counter mapping. While we were not entirely successful in this regard, the questions we raised through it are powerful enough to be heard by diverse audiences unrestricted to the halls of scientific and research institutes. Through the course of the project, we explored different ways to express the same stories along with the people who have been narrating it everyday, but who haven’t received the space to be heard.

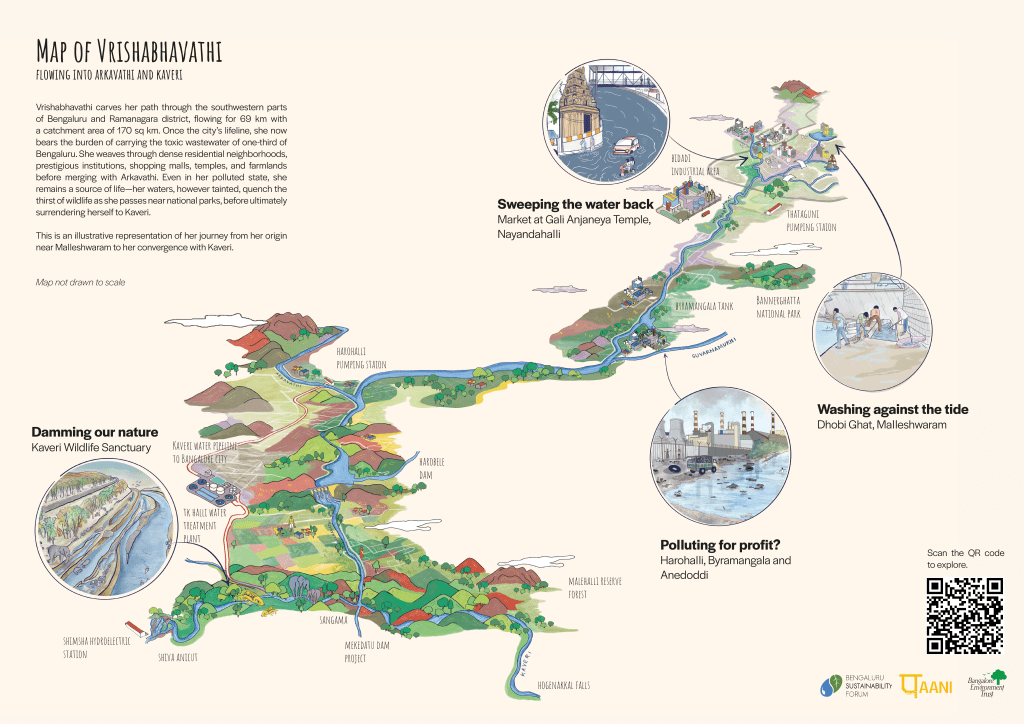

Vrishabhavathi is a key tributary of the Arkavathi. She is formed by the large catchment area to the west of Bengaluru, where several smaller keres and kaluves feed into her. Springs at the Kadu Malleshwara and Dodda Basavanna temples are believed to be origin points of Vrishabhavathi. Her name, derived from the Sanskrit word ‘Vrishabha’ (Bull), is linked to her perceived origin at the feet of the Nandi statue at the Big Bull Temple in Basavanagudi. Once known for her pristine waters, she played a central role in human settlement and religious life, leading to the establishment of several temples along her banks, including Dodda Ganesha, Gali Anjaneya, and Gavi Gangadhareshwara.

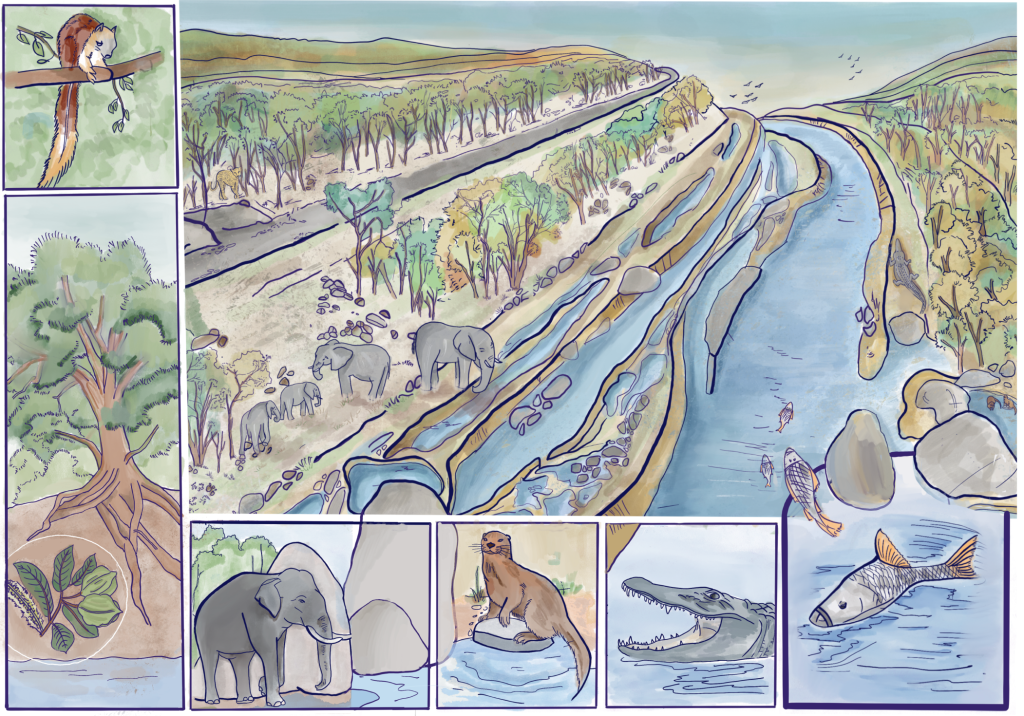

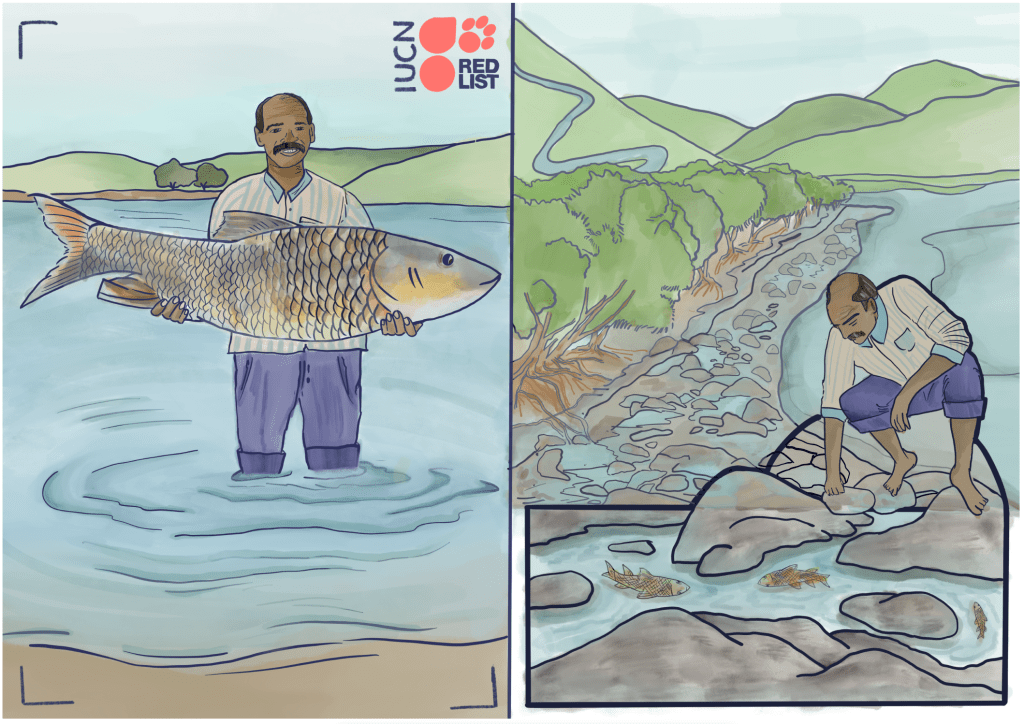

Today, Vrishabhavathi carves her path through the southwestern parts of Bengaluru and Ramanagara district, flowing for 69 km with a catchment area of 170 sq km. Once a lifeline, she now bears the burden of carrying the toxic wastewater of one-third of Bengaluru. Flanked by industrial hubs in Peenya, Yeshwanthpur, Kumbalgodu, Bidadi, and Harohalli, she weaves through dense residential neighbourhoods, prestigious institutions, shopping malls, temples, and farmlands before merging with the Arkavathi river. Even in her polluted state, she remains a source of life—her waters, however tainted, quench the thirst of wildlife as she passes near national parks, before ultimately surrendering herself to the Arkavathi near Kanakapura town. Labeled ‘critically polluted’ by the pollution control board, Vrishabhavathi has been stripped of recognition as a living system. Over time, she has been overwritten by waste and neglect, her presence diminished by the promise of piped water from the Kaveri.

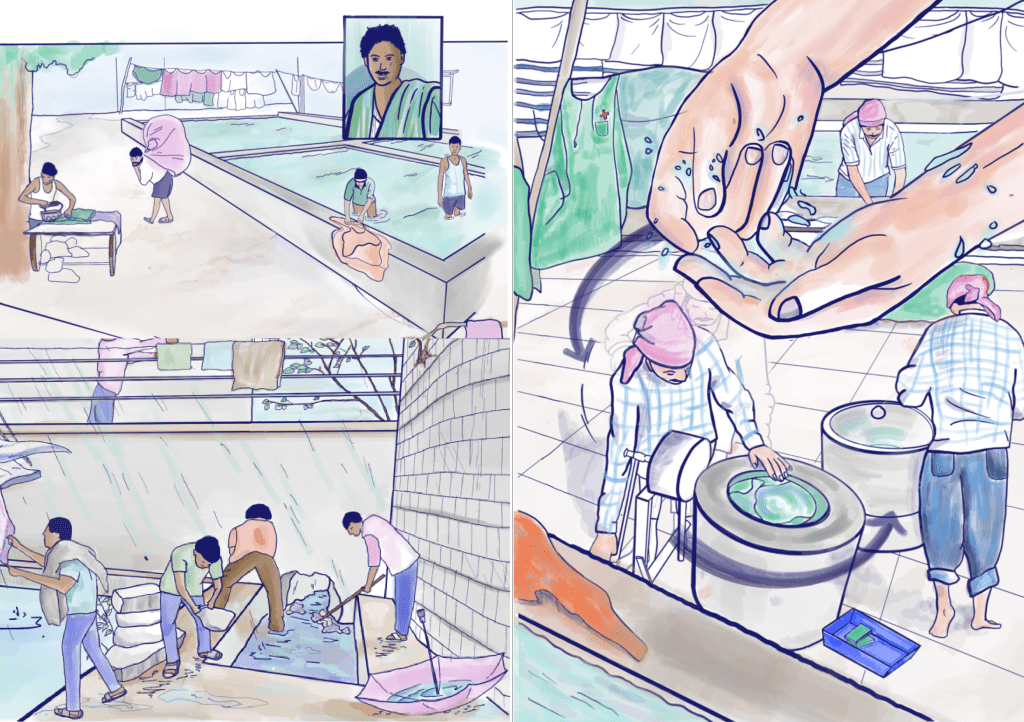

1. Washing against the tide – Dhobi Ghat, Malleshwaram

“..When there was no city, we could see Vrishabhavathi Nadi flow between the two hills that make up our valley…”

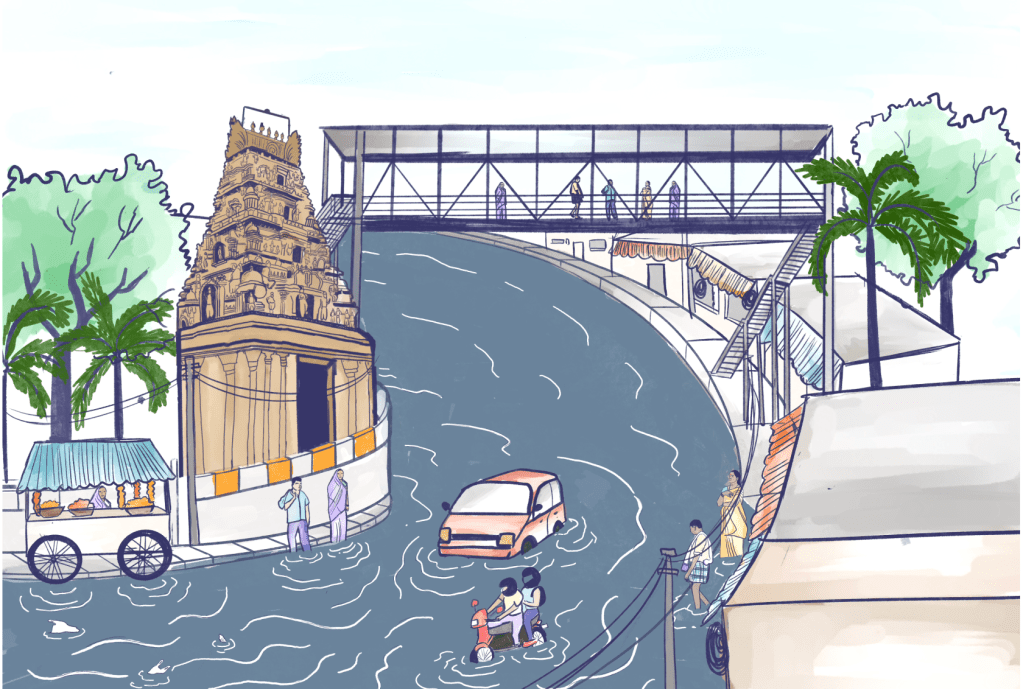

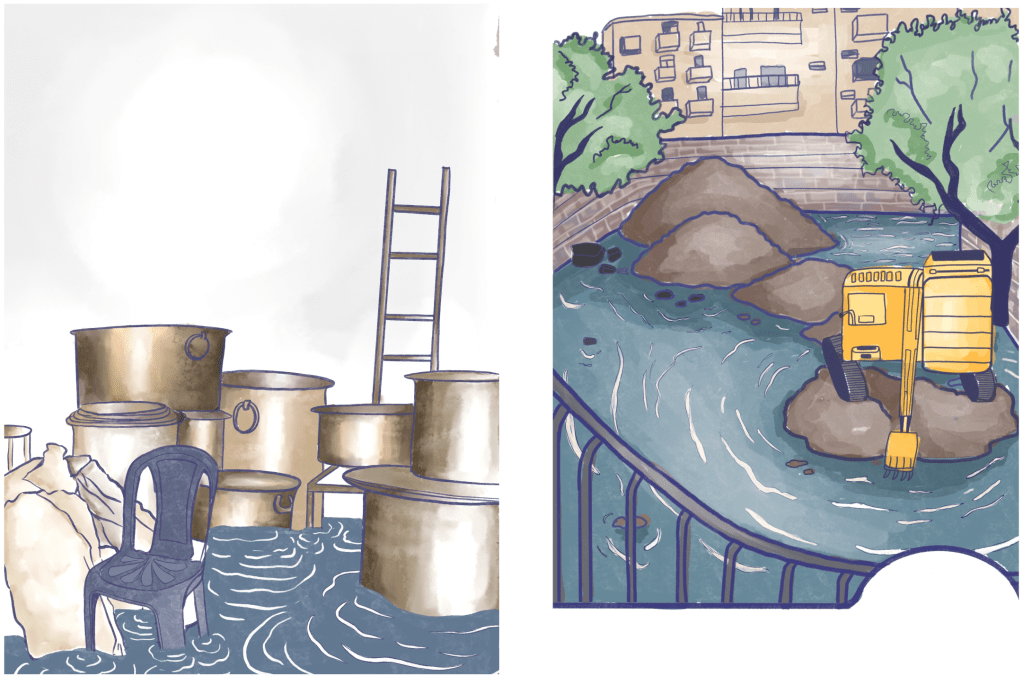

2. Sweeping the water back – Flooding in the markets of the Gali Anjaneya temple, Byatarayanapura

“Every time the river comes into our shop, we incur huge losses. We have to close the shop and sweep the water back into the streets.”

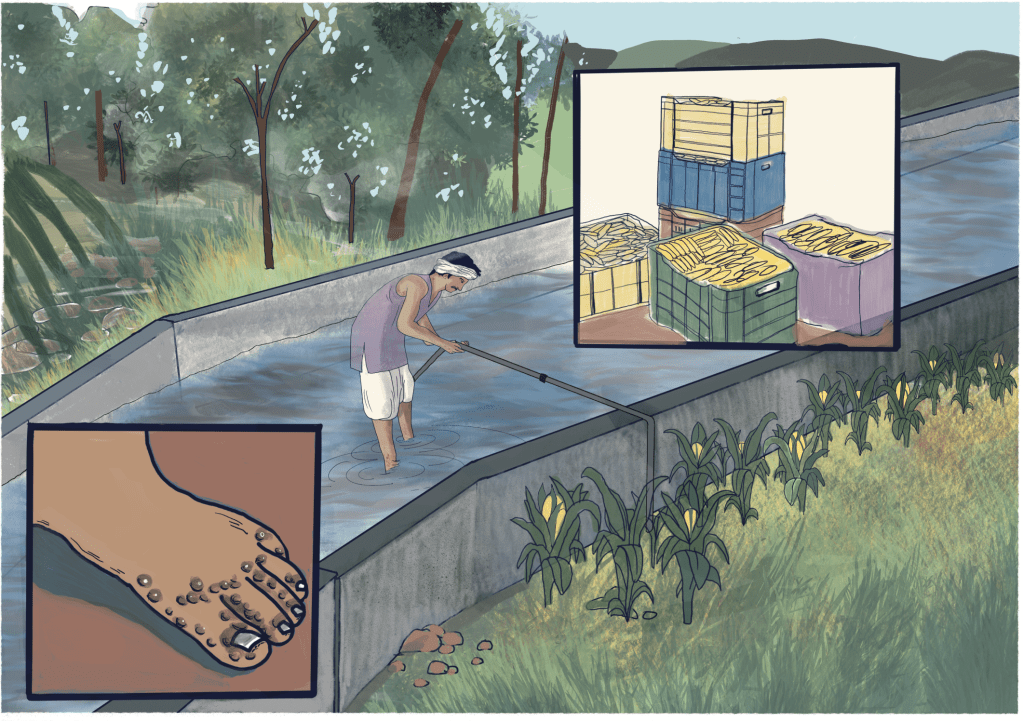

3. Polluting for profit?

“I want to draw Vrishabhavathi Nadi using the colour blue…”

4. Damming Nature, Kaveri Wildlife Sanctuary

“Do we really need the massive Mekedatu Dam or can we imagine other solutions for water? What stands in the way of these less invasive solutions?”

Read more about our process on our website.