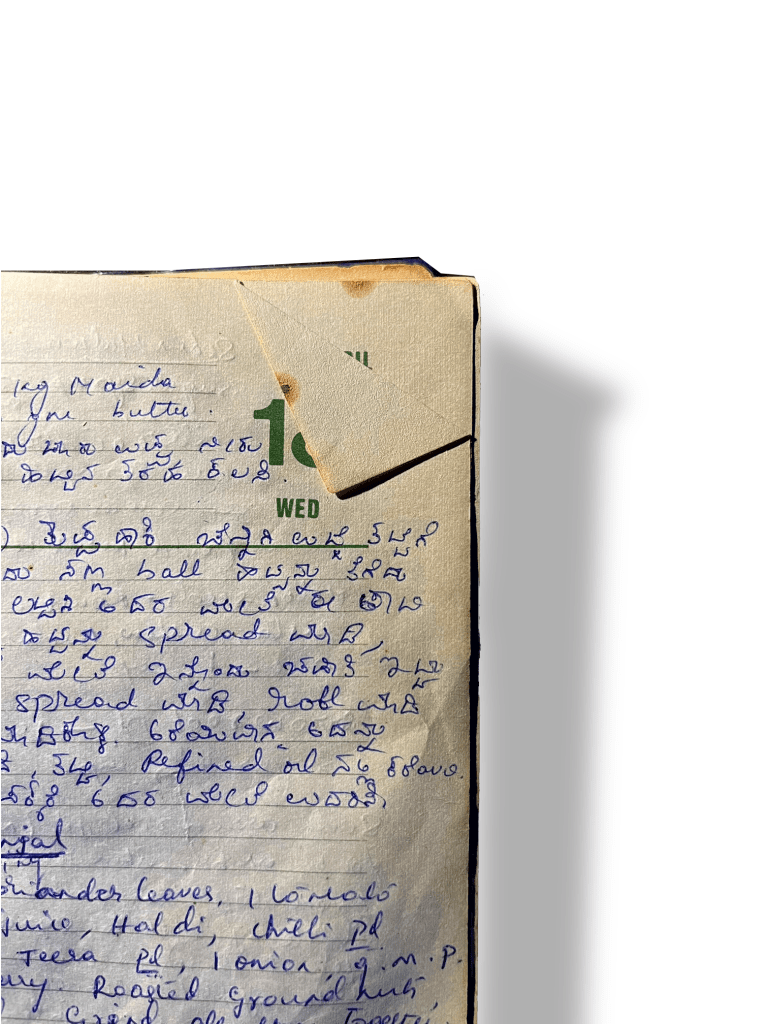

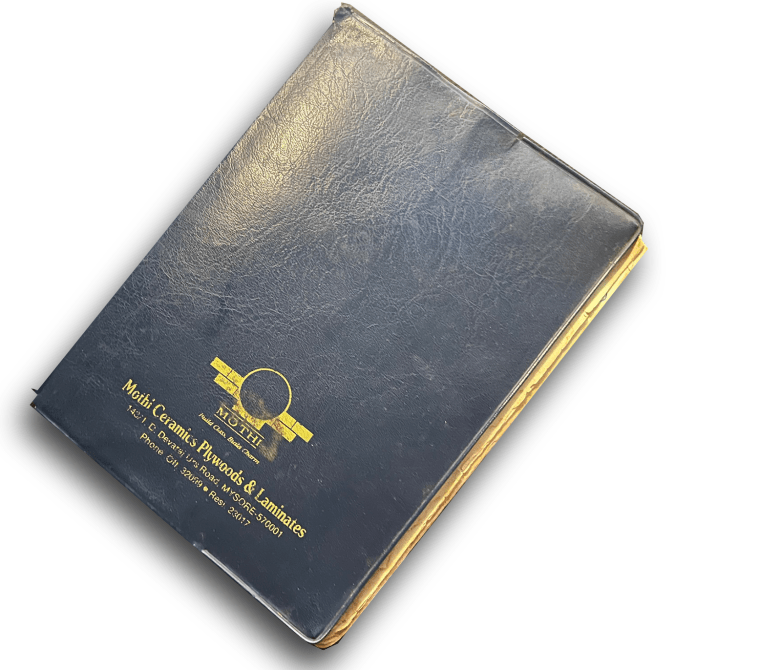

I am flipping through Amma’s recipe book this evening. The pages are populated by a mix of Kannada and English words scribbled in haste. Most of it is illegible to me, partly because I’m a terribly slow Kannada reader but mainly because it’s a language my mother shared with her mother, her neighbour and herself. She can make out exactly what her shorthand of the time was, a cipher she hasn’t passed to me. In her words, ‘Why do you need this tattered book? You’ve got YouTube.‘

This recipe book, to me is more than what any video can offer. When I first scanned the pages, I felt like an intruder, prying into those moments she stood next to Jaggu Aunty as she laboriously demonstrated every single dish she thought Amma should know, making sure she took down detailed notes to replicate them at home. I could even sense the whispered anticipation of their conversations as they decided what dishes might be better than others to cook for her new husband. ‘Jaggu Aunty (Jaggu being the name of her husband, she’s known to us all as this, I cannot recollect her name) taught me a few dishes when my marriage was settled.’ I have heard a lot about her and her family and have met them a few times, the family that cared for her as if she were their own daughter. It is a journal of Amma’s few months of engagement and early years of marriage, though she doesn’t see it that way because when I ask her if I can read it, she laughs and says, ‘It only looks like a diary, it isn’t one.’

These pages tell me what she was aspiring to, what drew her fancy and how often she immersed herself in it. It is not a straightforward documentation of events, but the notes crawling on the sides about how to adjust serving sizes tells me how many people she had to cook for and the time it would have taken her to do all those dishes after the meal was done. The language in which she’s written tells me where she drew her recipes from or how comfortable she is with the cook that’s demonstrating them. A few pages have a different hand. I wonder aloud if she was testing that too. ‘No‘, she says, ‘Jaggu Aunty went to great lengths to help me, that’s her handwriting. It’s a steadier hand, devoid of errors, see,’ she points at the words. I don’t agree. Errors here mean that there is room for exploration, trials of small and grand scales.

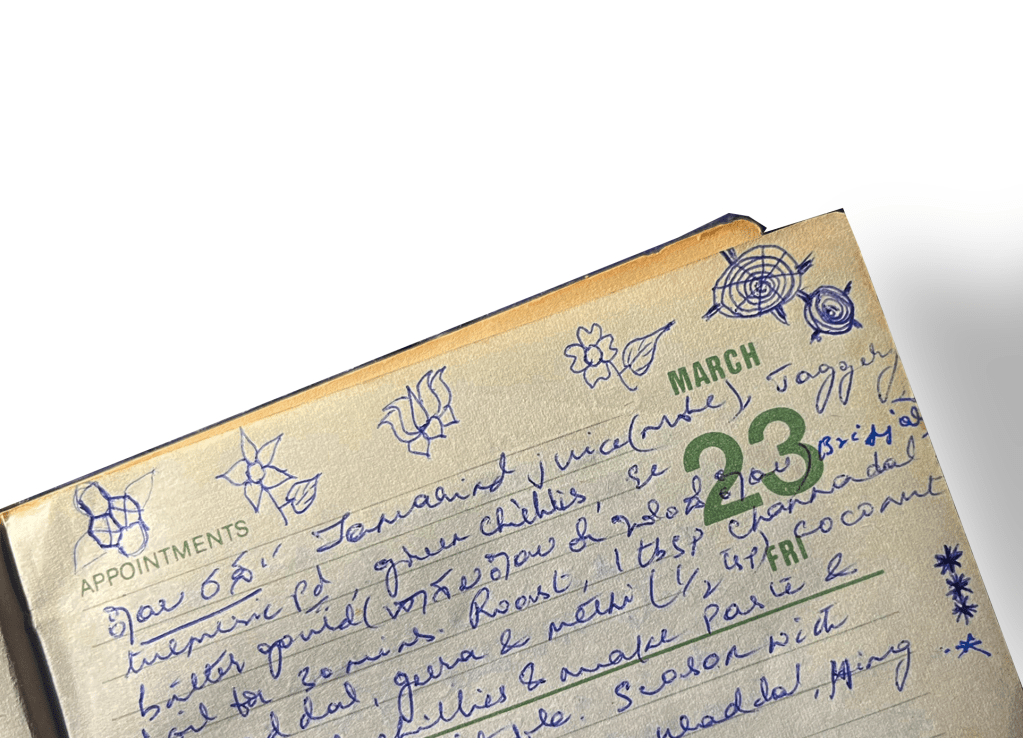

She has dog eared some pages, I can tell these are recipes she goes back to even now, since I am familiar with how they taste rather than how they look on the page. These are where her memories lie in the food she cooks. We all have loved the stuffed badnekai subji she makes, and the book is a silent observer and documenter of that. The pages in which the ink has run and bled and the chutney spread, speak to the moments of doubt where she relies on the recipes since otherwise, she thumbs through them memorizing all the steps before starting a dish. The slight quiver in her road runner attitude in the kitchen. I, on the other hand have multiple tabs open on my phone to check and counter check my measures and ingredients. In all my years, I can count the number of times I have seen the book on the kitchen counter, on my fingers. As I write this, the mixer is whirring coconut into fine powder that’ll go into the sweets for the Habba tomorrow. I pause to offer my hands of service already knowing her answer. When she’s done turning me down, I open the page in which she’s written the recipe for Kargadabu, the sweet she’s preparing. Caringly written words, illustrating how to make it leave me pondering. She spent her time learning all these new dishes knowing she’d be cooking them for herself and her husband, a man she was yet to know. What must she have been thinking at this time? ‘Were you anxious of what lay ahead?‘ I ask her. ‘I was, of course, but it was something for me to look forward to and all this was a way to prepare,’

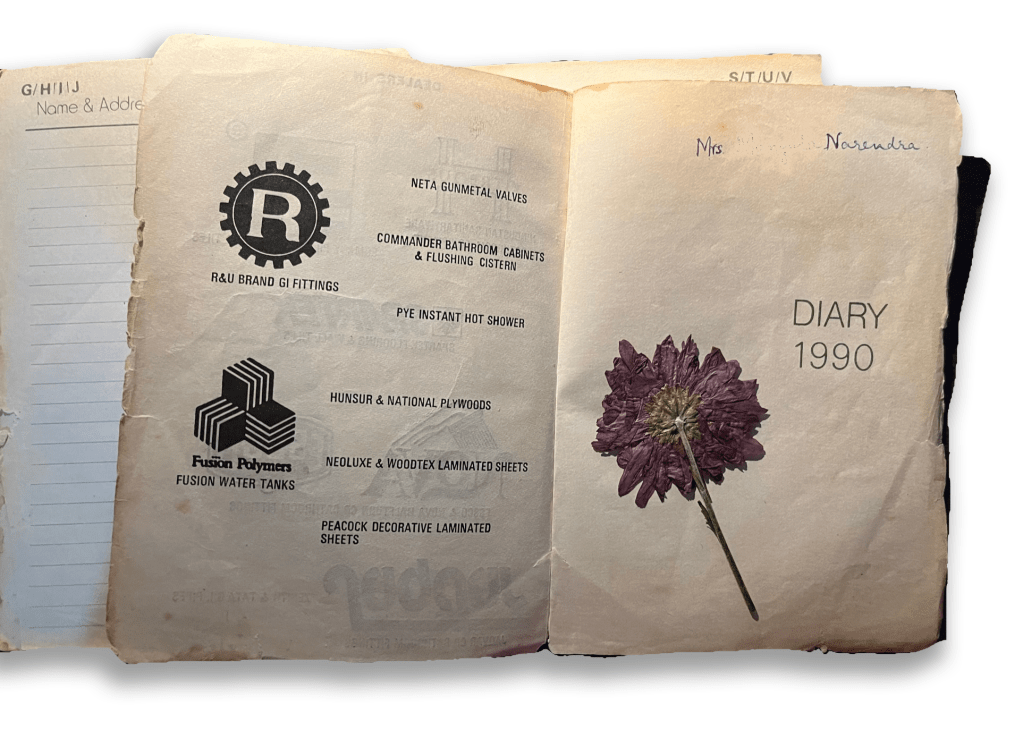

I turn the book a few times and I notice that it is an old diary from 1990 (gifted by Jaggu Aunty), a few years before she got married. The address reads: Devaraj Urs Road, Mysore. Her home, my home (away from Bangalore, the city I was born in). This book has Macaroni Mexican sitting below Paratha. I can smell and feel her tastes shifting as she writes, picking and choosing from the array of delicacies demonstrated on cooking shows. A few years later, amidst the English text sit Eight Jewel Vegetable and Lotus leaf rice. I don’t remember her having made these, but they stick out of the pages (literally too, I need to find a way to preserve this book) because she had wanted to, at some point. Mysore to Saudi to Bahrain and finally to Bangalore, the book has survived all.

The last page of the book, written in Jaggu aunty’s hand reads: Mrs. Narendra. I think she was testing out with Amma how her new name would feel. While I’m closing the book, I find a page with scribbles all across the recipe, a sign left behind by a meddling child with a pen. This book has not just documented Amma’s time around the house, but our (my brother and I) times on the kitchen counter or on the floors as Amma rustled up meals for us, fed us, nourished us in more ways than just through the stomach and bookmarked the dishes we favoured. I am unable to tell what her favorite is amongst all the recipes, something she doesn’t give away very easily even now.

I have a complicated relationship with food, one Amma still doesn’t understand. But through her food diary, I have understood parts of her we haven’t spoken about before. She mentions to me as I tell her I am writing this post that her Amma, my Ajji, has contributed to the extensive pudi, chutney and gojju section in the book. Through this, I have discovered a shared love for documentation and writing (and doodling). I say a silent thank you to Jaggu Aunty and my Ajji for collaborating on a journal that I know my mother spent years writing in, hours poring over and moments cherishing as she continues to read it. She hasn’t written in it for years now. Much as she denies, she’s a child of YouTube too.

Leave a reply to Shivani Cancel reply